By Zack Beauchamp

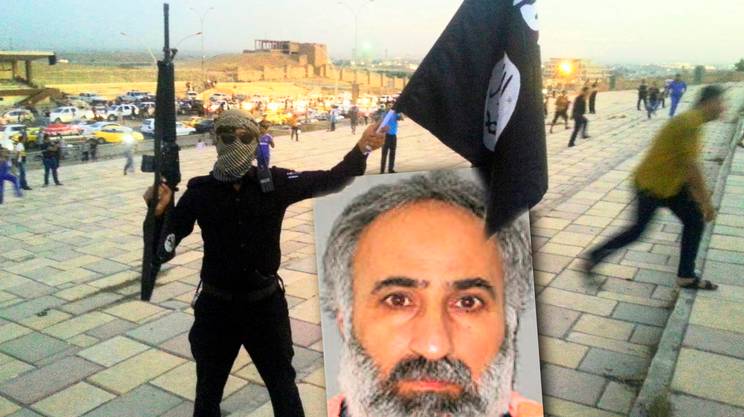

On Friday morning, a US air strike killed Abu Alaa al-Afri, a senior leader in ISIS, whom the US says it considers the organization’s second-ranked leader.

This isn’t the first time that al-Afri has been reported dead — though the US government has allegedly verified his death.

But if (as seems likely) al-Afri is dead, this will be yet another instance in which ISIS’s number two official has been killed. In August of last year, for example, a US airstrike killed Fadhil Ahmad al-Hayali, then identified as the group’s number two.

This continues a trend that news consumers may recognize from counterterrorism efforts against al-Qaeda, in which the group seemed to lose one third-in-command (after Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri) after another.

As some Twitter wags noted, this all hearkens back to a 2006 Onion article, “Eighty Percent Of Al-Qaeda No. 2s Now Dead.”

But what’s actually going on here? Why is the US killing so many ISIS deputies, while somehow failing to hit leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi? And it does it even matter when you kill top-level ISIS officials?

Why the US keeps killing number twos

Analysts have developed a few theories as to why the US keeps hitting second-in-commands, but not the leader. One of the most plausible is that Baghdadi is a much harder target, whereas the nature of the number-two job involves exposing oneself to greater risk of being targeted.

As a leader, Baghdadi serves as ISIS’s chief executive and ideological head. He doesn’t actually have to move around all that much or actually go out in the field; his job mostly involves issuing orders and, on occasion, making propaganda tapes.

That means he can sit wherever he’s hiding out, avoiding the kind of contact with the outside world that makes it easier for US intelligence agencies to find you.

However, not every ISIS leader has the luxury of doing that. Baghdadi’s top subordinates, the ones he gives orders to, have to go out in the field and run ISIS operations. If you command a major combat theater in Iraq, for example, you actually have to be in that part of Iraq. If you run ISIS finances, you need to make sure that its extortion and oil operations are running smoothly.

When you’re out actually doing the work — managing ISIS outposts, talking to people lower down on the food chain — you can’t hide away like Baghdadi does. That makes it easier for US electronic, satellite, or human intelligence assets to find you — and serve up targeting data for an airstrike.

This difference in responsibilities probably explains why the US, despite targeting Baghdadi multiple times, the US hasn’t managed to kill him — and yet has successfully taken out many of his deputies.

“That would be my guess,” Will McCants, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me.

Does killing leaders actually matter?

While the US government is understandably trumpeting its alleged strike on al-Afri, there’s reason to suspect that killing the group’s number-two isn’t actually all that consequential.

Groups such as ISIS and al-Qaeda are bureaucratic by design, and so they are often able to deal with drone-struck senior officers by rapidly promoting up new people to replace them.

This theory got some quantitative support in a 2014 study by the University of Georgia’s Jenna Jorden, who found that so-called “decapitation” strikes — in which the US killed a senior leader of a terrorist group — had little effect on reducing violence from that group.

In the paper, Jordan argues that this is because al-Qaeda is a bureaucratic organization: It has has something like a formal command structure, division of labor, clear assignment of responsibilities, and the like. This allow lower-level leaders to take over after one is killed.

And this would likely apply to ISIS as well.

“Each individual decapitation doesn’t cripple the organization,” Daveed Gartenstein-Ross says, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, told me.

So al-Afri’s killing probably will not, in itself, be that consequential for ISIS’s future.

That said, Gartenstein-Ross pointed out that al-Afri had “strong connections within the al-Qaeda network.” ISIS and al-Qaeda are at war in Syria, which distracts and thus weakens both of them, and there is little reason to believe that this is changing.

But Gartenstein-Ross points out that the possibility of rapprochement, while already quite low, may have just gotten a little lower with al-Afri’s killing.

“Given his connections, [there was] a danger that he could be involved in rapproachment between al-Qaeda and the Islamic state,” he said.

However, the ideological and personal gaps between the two groups will likely remain too far to bridge anytime in the near future. That would have been true even if al-Afri had lived. So al-Afri’s death is probably not a substantial change for ISIS’s prospects.