By John Cassidy, New Yorker

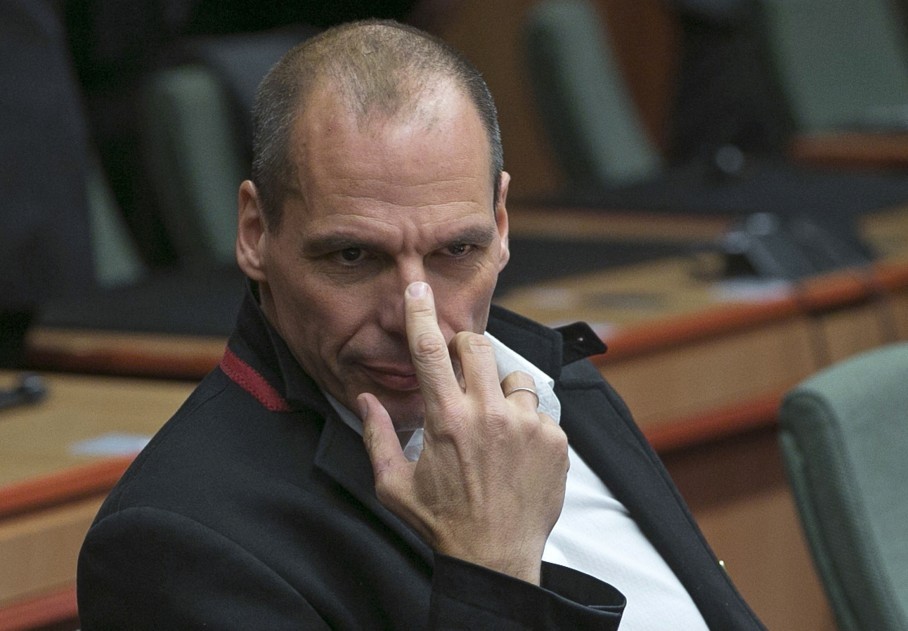

he news that Greece’s controversial finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, has been shuffled out of negotiations with the country’s creditors, in favor of a team led by the deputy foreign minister Euclid Tsakalotos, evidently pleased the European financial markets:

on Monday and Tuesday, stocks moved higher and yields on Greek bonds fell sharply. With the outspoken game theorist no longer participating in the talks, investors are betting that it will be easier for the two sides to reach a compromise that will prevent the government in Athens from going bust and crashing out of the euro zone.

In the short term, the move may well help. The Greek government is virtually out of cash, and relations between Varoufakis and his European counterparts had deteriorated to such an extent that his continued presence was a barrier to a deal to release the $7.2 billion in new loans pledged by the European Union back in February, contingent on an agreement for a Greek reform program. Kicking Varoufakis upstairs—he is staying on as finance minister, and will continue to oversee the negotiations—may well make it easier for both sides to make compromises.

In a lengthy television interview on Tuesday night, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras expressed confidence that a deal could be reached by May 9th, which is a few days before Greece is due to make a big payment to the International Monetary Fund. “Despite the difficulties, the possibilities to win in the negotiations are large,” he said. “We should not give in to panic moves.” Tsipras also ruled out calling a snap election, an option that has been mooted recently. But he did raise the possibility of holding a referendum if Greece was forced to accept terms that went outside Syriza’s anti-austerity mandate.

On the basis that neither side wants Greece to leave the euro zone, I’ve argued all along that some sort of deal would probably be reached at the eleventh hour. Reports from Athens suggest that it will consist of the Syriza government submitting legislation to enact some of the reforms that the European Union wants, such as the introduction of a uniform value-added tax and the privatization of state-owned assets like ports and airports. In return, the E.U. may let slip, for now, some of the other things it has been demanding, including changes to Greece’s pension system and labor laws.

But these issues won’t go away, and neither will Greece’s financial crisis. At this stage, indeed, the extended dispute over the $7.2 billion is starting to look like a sideshow. Come June, the two sides will have to reach a separate agreement on restructuring, or refinancing, the Greek government’s overall debts, which total about a hundred and seventy-five per cent of the country’s gross domestic product. Based on what we’ve seen during the past few months, the chances of those talks reaching a successful resolution are slight.

What is needed, most objective analysts agree, is a big write-down in Greece’s debts and a new policy regime that restores economic growth: that’s how almost all sovereign-debt crises get resolved. In this case, though, the 2010 bailout, which was revised in 2012, didn’t impose any write-down on Greece’s lenders, which were, primarily, large financial institutions. Designed by the troika—the E.U., the I.M.F., and the European Central Bank—the bailout “was about protecting German banks, but especially the French banks, from debt write-offs.” (That wasn’t Varoufakis speaking: it was Karl Otto Pöhl, a former president of the German central bank.) In addition to saddling Greece with an unsustainable debt burden, the troika obliged the government in Athens to slash spending and greatly reduce its ballooning budget deficit. It succeeded in those aims, but at great cost to the rest of the Greek economy. Between 2010 and 2014, the G.D.P. fell by about a fifth, and the unemployment rate rose to more than twenty-five per cent. The bailout caused a depression inside Greece.

To people who follow Greece closely, this story is familiar, but it bears repeating. Since taking over as finance minister, Varoufakis has at times engaged in wishful thinking, stonewalling, and self-dramatization. (On Sunday, he tweeted a quote from a 1936 speech by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, describing his political enemies as “unanimous in their hate for me; and I welcome their hatred.” Varoufakis added: “A quotation close to my heart (& reality) these days.”) But the arguments that Varoufakis has been making about Greece’s plight, and about the damaging impact of the austerity policies that accompanied the 2010 and 2012 bailouts, are incontrovertible.

Sadly, there is still no sign that the leaders of the E.U. are willing to acknowledge these truths, a problem that Athanasios Orphanides, an economist at M.I.T. who formerly served as the governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus, laid out very clearly earlier this year. Why are the Europeans being so stubborn? It’s not simply a matter of faulty economic analysis, although there’s some of that. The main problem is a political one. Having forced the other member countries that have received bailouts—Ireland, Portugal, and Cyprus—to swallow the austerity medicine, the E.U.’s establishment (and many of its member governments) is loath to do anything that seems to give Greece, and particularly Syriza, a break. One way to avoid this difficulty might be to adopt an E.U.-wide policy designed to reduce indebtedness, such as the debt-buyback proposals contained in a new report from the London-based Center for Economic Progress. Bur rather than moving in this direction, policymakers in Brussels and Frankfurt are sticking to the pretense that Greece will eventually be able to repay all of its loans.

If that sounds pretty dire, that’s because it is. Greece is in a horrid situation. And sidelining one awkward customer hasn’t changed that.