Two new, anti-establishment parties (including one that grew out of the indignados movement — a kind of Spanish precedent to Occupy) took key seats in regional and municipal elections in yesterday’s Spanish election, which is a kind of dress rehearsal for the upcoming national elections.

Meanwhile, in Greece, the Syriza anti-austerity government has been in power for about four months, and has largely held the line on its refusal to sacrifice human rights, pensions and social programs to satisfy its IMF, EU and World Bank creditors. As a result, they are set to default on their loans as early as next month. This would likely mean that Greece would stop using the euro and restore the drachma, wiping out the majority of its debts in the process. Germany, one of Greece’s largest (and most intransigent) creditors did a similar thing upon reunification in 1990, when the new Germany defaulted on its debts to Greece.

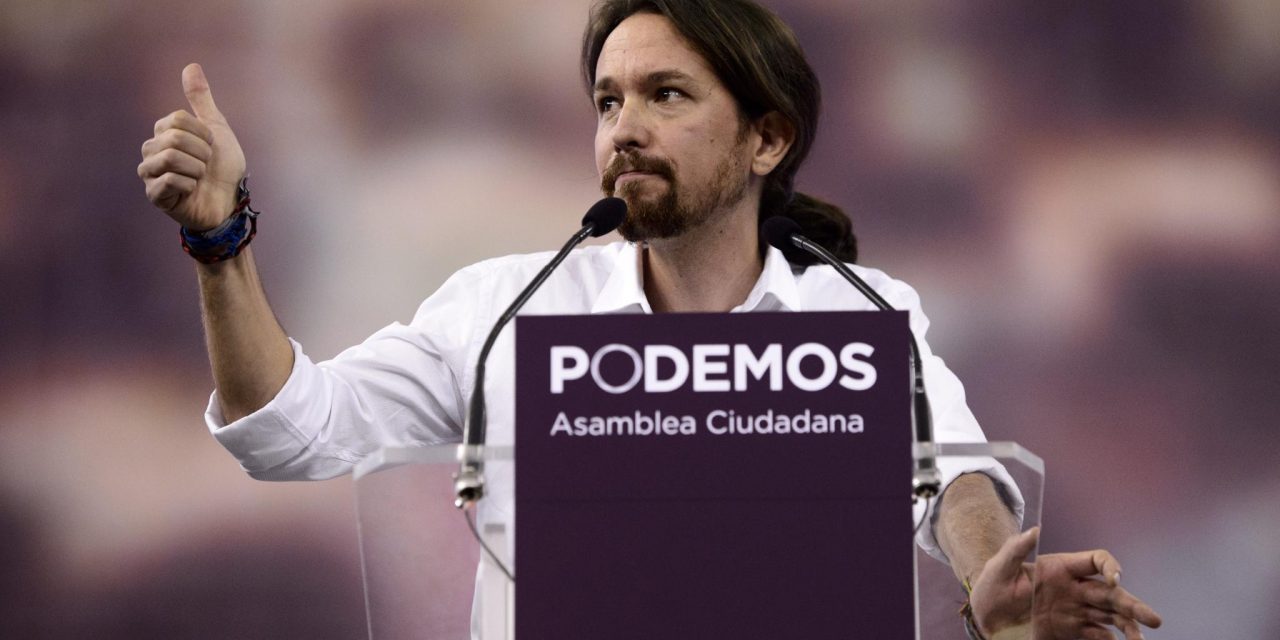

The new crop of Spanish regional and municipal leaders are drawn from Podemos, an anti-austerity, left wing party; and Ciudadanos, a center-right party. They clobbered many of the previously safe seats that had belonged to the ruling People’s Party for decades. In Barcelona, the new mayor is an anti-eviction activist. Madrid’s mayor, an aristocrat who idolizes Margaret Thatcher, may lose to a coalition led by a socialist retired judge.

Spain will hold its next general election in December. The Greek debt and austerity situation will redound through the Spanish political scene between now and then. If the troika crush Greece for its insistence on people before usury, the Spanish anti-austerity movement will be able to use their situation to drive hostility to austerity’s advocates and sympathy for renegotiation of its debts. If the troika allow the Greeks to renegotiate, Podemos can use this to soothe Spaniards’ fear of punishment if they take on their debts.

Complicating matters are Spain’s separatist movements in Catalan and Basque country. The Catalan independence movement has only strengthened since the beginning of austerity, its leaders arguing that rule from Madrid imposes economic hardship on the region. The central government has responded with brutal crackdowns on the separatists, including high-profile cyberattacks on the movement’s electronic communications and infrastructure. These high-handed tactics only make the Catalonians’ point that the central government is unfit to rule.

The Greek interior minister, Nikos Voutsis, a long-standing ally of the prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, insisted the country was near to financial collapse. In an interview with Greek television station Mega TV he said Athens needed to strike a deal with its European partners within the next couple of weeks or it would default on repayments to the International Monetary Fund that form part of its €240bn rescue package.

Voutsis said: “This money will not be given and is not there to be given.” His comments came as the finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, repeated his warning that the entire euro project would be undermined without a deal that proved acceptable to the Greek people. Varoufakis told the Andrew Marr show that the Syriza-led Greek government has now “made enormous strides at reaching a deal”, and that it is now up to the European Central Bank, IMF and European Union to do their bit and “meet us one-quarter of the way”.

With crucial debt payments looming, combined with the need for Athens to find around €1bn to pay public sector wages and welfare payments in the first week of June, the eurozone appeared to be entering the final chapter in its dispute with Greece. Tsipras wants the EU, ECB and IMF to release a blocked final €7.2bn tranche of the bailout without imposing tough reforms and spending cuts agreed with the previous right-of-centre administration.