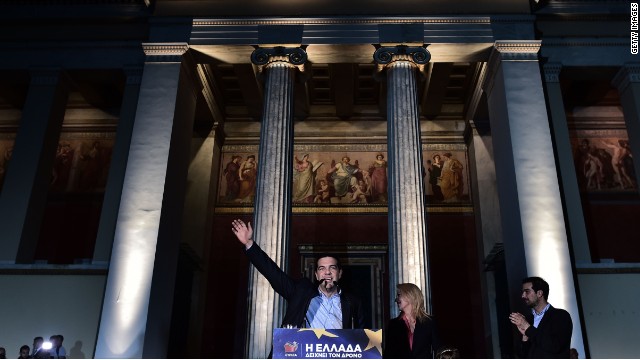

Greece’s new government must tread carefully with its EU partners

Financial Times

Everyone needs to take a deep breath and calm down. The apparent sense of shock is unwarranted. Syriza has done little more in office than it promised in the campaign. That said, it has proved itself poor at communicating its policies, and has started out with disturbing gestures towards placating its core vote rather than embarking on a broad policy of reforming the state.

As it happens Athens then meekly voted for extending existing sanctions and considering tighter measures next month. But if all ended well, the prospect of a major diplomatic row needs a swifter and more definitive response than a finance minister blogging about it two days after the event.

Such slips may be put down to uncertainty in a party with no previous experience of office. Other announcements, though, are more alarming. Syriza chose its first week to declare that it would halt privatisation of Piraeus port and the Public Power Corporation.

The relevance of this is not that such privatisations are utterly indispensable to growth in the Greek economy. It is that the Piraeus dockworkers and the PPC are political clients of Syriza. If the government is concerned about the treatment of dockers, for example, the solution is to enforce employment regulations, not to keep an inefficient company in public hands.

Indeed, one of the more peculiar aspects of the election has been the jubilation of some leftwing politicians and commentators in the rest of the EU and beyond, who appear to regard Syriza as standard-bearers for a resurgent European left. In reality — as symbolised by Syriza’s coalition with a far-right party — Greece’s problems are not ideological. Rather they involve entrenched interests throughout the economy and a clientelist tradition that aims to buy off particular groups rather than governing for the nation.

Politically and even economically, for example, Syriza may be right to start its clampdown on tax-dodging with what it and other Greeks call the “oligarchs” who dominate favoured companies. But it cannot end with the rich: evading tax is endemic throughout Greece’s economy.

No matter what happens with the debt and the target primary fiscal surplus, Syriza is facing a hard slog trying to reform a low-productivity economy riddled with rent-seeking and regulation. It is obvious that it will need relief on its sovereign debt and its target fiscal surplus. But the government will not persuade the rest of the eurozone that debt cancellation and fiscal leeway are warranted if it merely continues to hand out favours to its core voters.

Investors’ response to Syriza’s first week looks an overreaction. But the new government is learning that, when balancing precariously on a fiscal tightrope, moves in the wrong direction can be deadly. The markets should give Syriza more time. Syriza should use it.