BY BORZOU DARAGAHI, Foreign Policy

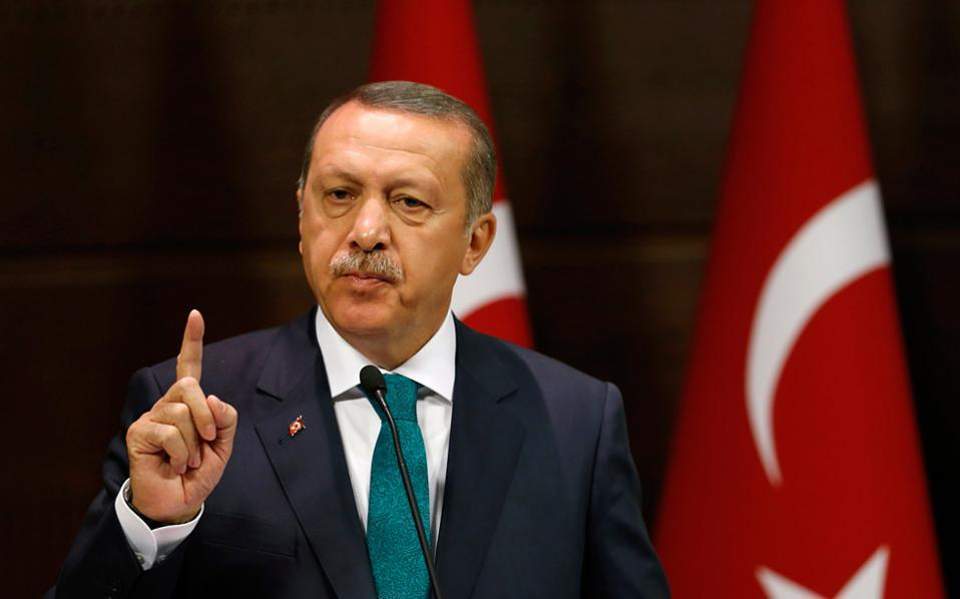

To Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s handlers, it must have seemed like a good idea at the time. Show off Turkey’s president to a group of London bankers and fund managers over a fancy lunch as a way to reassure nervous investors about the country’s economic stability and viability. After all, Turkey’s Central Bank had recently upped interest rates a higher-than-expected 75 basis points, showing a measure of fiscal prudence at a time of lingering questions about the country’s economic health.

But the May 14 luncheon and a subsequent interview with Bloomberg quickly went off the rails. Erdogan ranted against interest rates and raised doubts about the independence of the Central Bank, vowing even tighter control of the economy if he wins another full term after the June 24 elections.

Markets showed no mercy. Within 10 days, Turkey’s lira had plummeted to a new low, coming close to trading at nearly 5 to the dollar, compared to around 1.6 to the dollar in 2011, before the Central Bank raised a key interest rate by 300 basis points, from 13.5 percent to 16.5 percent. The move halted the slide and stabilized the currency, but it was not enough to quell worries about Turkey’s economy. After rallying briefly on Wednesday, the lira slid again on Thursday. Erdogan’s words had resounded deeply and negatively among already nervous investors.

“The suggestion that going forward that he would be looking to take more control of monetary policy and jeopardize the independence of the Central Bank has been an issue for market participation for some time,” says Paul Greer, a London-based portfolio manager specializing in Turkey and other emerging markets at Fidelity International. “If Erdogan’s goal was to appease investors and stabilize the currency, it achieved quite the opposite result.”

Financed by cheap international credit and enthusiasm for emerging markets, Turkey has grown spectacularly since Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party took over after another financial crisis in the early 2000s. Surrounded by figures like the technocrat Ali Babacan, a Kellogg School of Management graduate and financial consultant who for several years served as his deputy prime minister in charge of the economy, Erdogan was widely credited for following prudent economic policies that drew investment.

But as figures like Babacan have fallen away from Erdogan in recent years, things have taken a wrong turn. Turkey’s currency has lost 60 percent of its value over the last five years, dropping a dramatic 20 percent this year compared to the dollar. Turkey’s foreign debt has ballooned to $453 billion, and its current account deficit, the gap between its imports and exports, widened to $47.1 billion last year compared to $32.6 billion the previous year. Inflation is up, and consumer confidence is down.

Economists and investors say an overall decline in global appetite for emerging markets is hurting Turkey, but they also point to worries about Erdogan himself and his unorthodox views on economic matters. “His opinions matter a lot more than they did any time in the last 10 years,” says Paul McNamara, investment director at GAM Investments, a Zurich-based asset management firm. “In the past, he would say his thing. He was sounding off and providing political cover, and then the central bank would come out and raise interest rates. That’s no longer the case.”

Speaking to Foreign Policy, experts ascribed a number of economic principles to the president that they say don’t square with widely accepted standard notions.

“Interest is the mother of all evil.” Erdogan has repeatedly said he believes that high interest rates cause inflation, flying in the face of the economic rule that tightening the monetary supply reduces inflation. Some of his defenders say that his idea is rooted in the economist Irving Fisher, who held that a country could pull itself out of deflation by raising interest rates. Erdogan has been railing against the interest rate lobby since the beginning of his career, and financiers for a while gave him a pass as a politician cushioning the side effects of economic reality. Now, it’s apparent that Erdogan’s hostility toward interest is more philosophical, based in Islamic and Christian views of usury as sinful. What’s more, his vocal opposition to the wishes of his own Central Bank governors has worried investors about the independence of that institution.

“Many foreign investors over the years thought that Erdogan’s views of high interest rates was a standard politician’s criticism of rates,” says Inan Demir, an economist at Nomura, a Japanese financial holding firm. “But more recently, especially after Erdogan’s most recent statements in front of foreign investors in London, most people think it’s different, and it’s more deep-rooted in his belief system.”

Grow, grow, grow: Much of Turkey’s economic expansion over the last few years has been a result of a building explosion financed by easy credit that conveniently goes to construction and development giants that happen to be Erdogan’s political allies, by providing state loan guarantees and other tools to ease loans. His apparent belief in cheap credit is linked to a conviction that Turkey can grow without any limits and without overheating and exacerbating inflationary pressures. Erdogan seems convinced Turkey’s economy can grow at up to 7 percent annually without any side effects. But economists caution that unrestrained growth can actually hurl a country into a recession, with inflation — currently running at about 10 percent — eating into consumer savings and earnings. The International Monetary Fund and other economists say that Turkey should be growing at no more than 4 percent.