For Greece, 2018 is a crucial year.

The key question in the months ahead for what was once the epicenter of the European credit crisis is: Will it turn the corner and wean itself of external aid like Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus — something the Greek government wants? Or, will the current bailout program, which ends Aug. 20, be followed by a similar arrangement — as some observers expect?

“Things are looking better for Greece, having regained access to markets and with the recovery gathering speed,” Fabio Balboni, European Economist at HSBC Bank Plc in London, said in a Jan. 4 note to clients. “In 2018, the country might finally exit its bailout program, but a clean exit might prove challenging if the eurozone fails to deliver substantial and credible debt relief.”

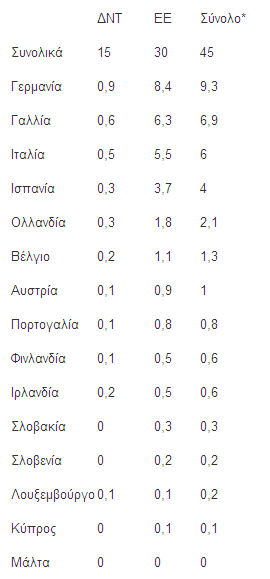

Since 2010, Greece has had three lifelines from euro-area countries and the International Monetary Fund with stringent conditions in terms of fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. It has also gone through two debt restructurings. In the next six-to-eight months, the Greek government and the country’s creditors have to work through some thorny issues if they want to avert yet another bailout program.

Here are the 10 crucial items on Greece’s calendar before the end of the bailout program:

- This week, the government plans to submit to parliament a bill to implement all the measures needed to conclude the third bailout review. New policies have to be voted on by Jan. 17 so that auditors monitoring the program can present Greece’s compliance report at the Jan. 22 Eurogroup meeting, which will then approve the disbursement of the next bailout tranche.

- In late January, European banking authorities will finalize the scenarios under which the balance sheets of Greek lenders will be stress-tested. The banks have to conclude these audits of their capital adequacy earlier than their EU counterparts.

- By early February, Greece intends to issue a new bond, with a maturity most likely of three or seven years, as it strives to regain full market access after years in the wilderness.

- During the first 10 days of February, the European Stability Mechanism is expected to disburse the bailout tranche attached to the implementation of the third review’s conditions. The amount of money Greece will get has yet to be agreed on, but it will be at least 5.5 billion euros ($6.6 billion), according to the Greek Finance Ministry.

- In February, Greek banks will start sending data to the Bank of Greece and European authorities for the stress tests.

- The Greek government expects that in February creditors will start discussing further debt relief measures.

- In early March, the fourth bailout review is expected to begin. It isn’t clear yet when creditor representatives will return to Athens, but the review has to start in March if Greece wants to complete another 82 measures on time.

- One of the most important gatherings between creditors before the end of the current bailout program will take place in Washington on April 20-22. The IMF’s spring meetings will probably give creditors the opportunity to discuss debt relief and what’s next for Greece.

- In early May, the stress test results will be announced. This will show if Greek lenders need more capital and, if so, how serious the problem is for them and for Greece.

- By the end of May or June, both the Greek government and creditors want to conclude the fourth bailout review and strike a deal on the conditions for any further debt relief and the post-program life for Greece. Greek authorities are ruling out any kind of new program, but the Bank of Greece’s Governor Yannis Stournaras recently said a credit line after August would boost investor confidence. European officials also say there will be some kind of “follow-up arrangement until 2022,” according to a person with knowledge of the discussions, since Greece has committed to primary budget surpluses of 3.5 percent of gross domestic product until then.

-

Exiting the bailout without any follow-up arrangement would create an annoyance for the country’s financial sector: it would mean junk-rated Greek banks won’t be eligible for a waiver allowing them to pledge sub-investment grade sovereign assets as collateral for the ECB’s normal refinancing operations, which provide the country’s lenders with around 13 billion euros in liquidity. This means that once Greece is no longer in a bailout program banks would have to convert some of that into Emergency Liquidity Assistance, which carries a 150-basis-point penalty over regular credit lines.

Tough Sells

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s administration will have to fulfill a politically difficult privatization program as it seeks to boost growth and gain the trust of investors needed for a bailout exit.

The Greek government projects that in 2018 it will manage to get 2.73 billion euros from the sale of state assets. But creditor estimates are more conservative and see the government falling short of its expectations. The country’s lenders are going to pressure the government to implement what has been agreed and bring in the projected revenues.

By June 2018, the government has to launch the tender for the sale of 17 percent of Public Power Corp., or find some other way to monetize its stake in the utility. By the end of the first quarter, it has to do the same for the sale of 30 percent of Athens International Airport, 65 percent of Greek state-controlled natural gas supplier Depa, 5 percent of Hellenic Telecommunications Organization SA and 35.5 percent of Hellenic Petroleum SA Greek authorities will have to complete by February 2018 key conditions needed for the start of the Hellinikon project.

Failure to meet targets may jeopardize government efforts to seek additional debt relief, as creditors will demand that the government does its part for lightening its burden before agreeing to additional concessions.

“What Greece has to do is stay on top of the reforms and if it does that, it creates space for the European Commission and the Eurogroup to discuss the big questions,” Mujtaba Rahman, managing director at Eurasia Group in London said.