The euro region agreed to give the country more money—and a little breathing space on debt.

The euro region’s finance ministers approved 8.5 billion euros ($9.5 billion) of aid on Thursday, and its most indebted state got a commitment that creditors will make sure it’s able to service future debt. If necessary, repayments can now be extended on emergency loans by up to 15 years.

While not perfect for anyone, it was a product of compromise. Germany agreed to come up with some figures on possible debt relief and to less ambitious budget targets. The International Monetary Fund then lent its credibility to the Greek bailout, if not its money. Greece got some cash and clarity.

Typically for these trade-offs, painful decisions were postponed and everyone will have to sit down again in a few months. But it feels like a question was answered, one that’s lingered since Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras clashed with Brussels over Greece’s crippling austerity two years ago: whether the country is a sustainable member of Europe’s single currency.

“It cements the perception that Greece will be taken care of, that whatever happens it won’t go to the sort of brinkmanship and real possibility of Grexit as we saw in 2015,” said Nicolas Veron, a senior fellow at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels.

Greece has been the eyesore on a map of renewed European stability. The continent’s populists have been all but seen off, the euro region’s economy is finally growing and countries are united in confronting Britain’s departure from the European Union. Yet the prospect of another fight with Athens over the country’s gargantuan debt still loomed in the background.

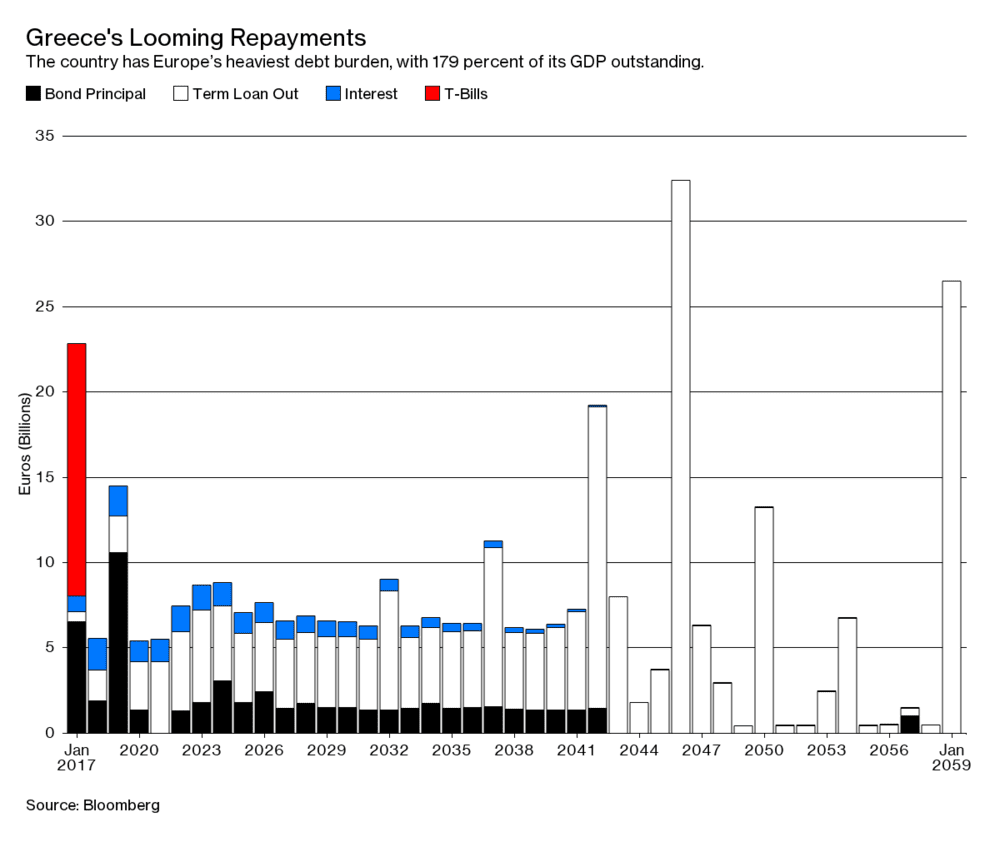

The issue has long been what do to with Greek debt exceeding 300 billion euros. That hasn’t changed, especially with German elections taking place in the fall. The IMF has advocated debt relief, which the Greek government has sought since coming to power in 2015. Euro finance ministers, led by Germany’s Wolfgang Schaeuble, have balked.

The problem now is that the Greek government raised expectations about a spectacular settlement that would pave the way for the country’s return to the bond market and free it from the shackles of the bailout programs.

Tsipras told reporters last month that he was expecting an agreement that would be “too good to be true.” In fact, he said, it would require him to wear a tie, something the premier declared he wouldn’t do until there was debt relief.

Instead, Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos flew back to Athens with a mixed bag, albeit one Greek officials were happy with because it represented some improvement from what they had on the table a month ago.

The disbursement of money is larger than originally expected and should allow Greece some breathing room. The deal also offers a roadmap on how debt could be eased, and a more manageable budget target than what some creditors were suggesting.

On the downside, the IMF remains to be convinced that Greek debt will become sustainable, effectively keeping the country out of bounds for the European Central Bank’s bond-buying program. It’s also unclear whether investors will start committing money when the latest bailout expires in August 2018.

Getting enough cash to avert a potential default on debt due in July, after months of edge of the cliff diplomacy, is still no small feat given the twists and turns in the Greek drama over the past seven years.

As Tsakalotos met Greek journalists at Luxembourg’s Le Royal Hotel, he complained about the lukewarm reception to the deal after they joked whether he could spare some change from the money he had secured for an evening drink. “I will buy you a drink when you finally get to write a word of praise,” he said.