by Frances Coppola, Coppola Comment

Ricardo Hausmann argues that Greek spending was “out of control” during the years prior to the Eurozone crisis – which as far as Greece is concerned actually started in 2009 with its first debt crisis, not in 2012 when the whole bloc nearly collapsed. He says:

Greece piled up an enormous fiscal and external debt in boom times, until markets said “enough” in 2009.

Since the world was in recession in 2000-1 because of the dot.com crash, we have to assume that by “boom times” he means 2002-6 (since the financial crisis in Europe started with the failure of IKB in July 2007). So is he correct?

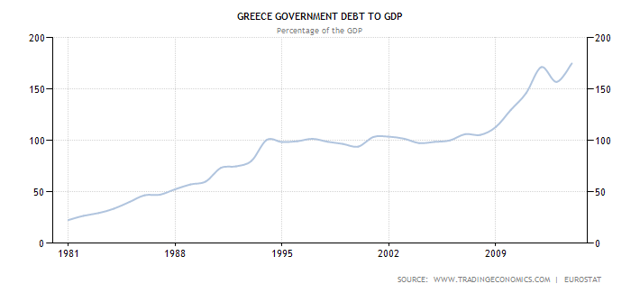

Here is Greece’s debt/gdp from 1981 to the present day:

Nowhere in this chart is anything indicating a vast increase in debt/gdp from 2002-6. The vast increases in debt/gdp occurred prior to 1993 and from 2009 onwards. Greece’s debt/gdp was high but stable from 1993 to 2009. Sixteen years of stable debt/gdp does not suggest a profligate government piling up an enormous debt due to out-of-control spending. It does suggest a government that was unable or unwilling to cut its debt/gdp in the boom times, but Greece is hardly alone in that.

Ok, so Hausmann is wrong about the external debt/gdp. Greece’s high debt/gdp did not come about during the 2002-7 boom. It dates from the recessionary 1980s.

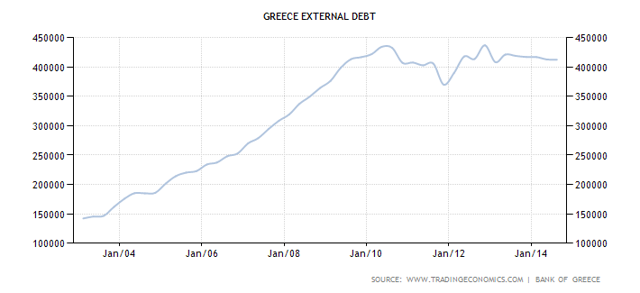

What about its external debt? Now there was indeed a huge increase during the boom times:

Which was of course because of this:

Yes, that is a large and growing trade deficit. The last time Greece’s current account was in balance was in 1995. Hausmann does have a point about Greece’s competitiveness. But the damage was done in the years from 1995 to 2001. During the boom years 2002-6 it appears that Greece’s current account deficit was actually shrinking. So again, Hausmann is incorrect. Greece’s trade deficit pre-dates the boom years.

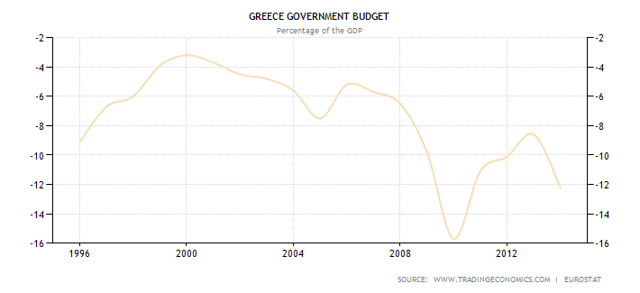

What about its fiscal deficit? After all, it does appear to have been servicing its debt without increasing it. Here’s Greece’s government budget to GDP:

Well, this is odd. Greece’s debt/gdp was stable until 2009 even though it was running a sizable budget deficit throughout that period. These figures are of course all ratios, so we need to look at what was happening to GDP during that time. Here’s Greece’s annual growth rate:

That’s really a rather healthy growth rate. No wonder Greece’s debt/gdp was stable despite its budget deficit. And no wonder no-one saw the crisis coming. Why would anyone think an average annual growth rate of about 4% for over a decade was unsustainable?

Hausmann’s claim that Greece built up unsustainable fiscal and external debts “during the boom times” is clearly wrong. The fiscal debt built up during the 1980s, and the external debt built up during the 1990s. Both were fed by recession. Profligacy there may well have been – but it was a long time ago. And there was no doubt a missed opportunity to reduce the debt burden. But should Greece really be blamed for failing to take advantage of an opportunity that just about every other government in the Western world missed?

Hausmann is also guilty of a cardinal statistical error. He says that “By 2007, Greece was spending more than 14% of GDP in excess of what it was producing, the largest such gap in Europe”. Indeed it was. But as the current account to gdp chart above shows, that 14% trade deficit did not gradually build up during the boom years, as Hausmann implies. Greece’s current account deficit actually started to decline in 2005, having improved from 2001-4:

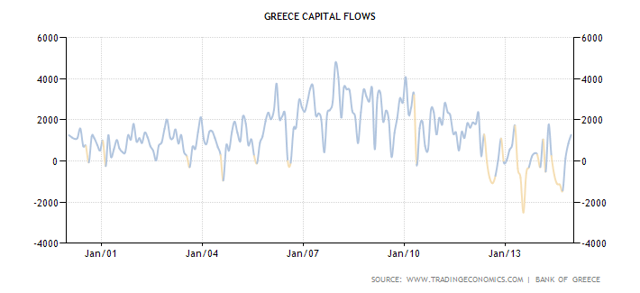

The mirror image of this is of course the increasing inflows of capital from 2005 onwards:

Any analysis of Greece’s external position that looks only at the current account deficit and ignores the growing capital account surplus is telling only half the story. Hausmann chooses his data to suit his argument that Greece’s problems are all due to its profligate government spending and lack of investment. He ignores the (substantial) role of capital OUTFLOWS from other countries in the Eurozone, notably but not exclusively Germany. And he ignores the fact that the period 2005-7 was characterised by a dangerous buildup of credit bubbles throughout the Western world.

I’ve written elsewhere about the Eurodollar (“US-in-Europe”) leveraging flow system that burst catastrophically in 2007-8. There was an equivalent Euro leveraging flow system circulating between the core and periphery Eurozone countries. This is what we are looking at in the chart above.

Capital has to go somewhere, and it has to be used for something: and that something is not necessarily productive. In Spain and Ireland, capital outflows from core countries blew up real estate bubbles. In Greece, they fuelled a consumption boom and enabled the government to maintain a high budget deficit. Is Greece’s use of those capital flows any more dysfunctional than Spain or Ireland’s?

And why was capital flowing to that extent at all? Why was it not funding commercial businesses in its countries of origin? Germany hardly has a stellar investment record either. The truth is that NO-ONE used that capital for investment. No-one at all.

Why are we not blaming this on the banks whose highly-leveraged, unproductive lending caused this collapse? We have been quick to blame banks for the “US-in-Europe” crisis. But we have blamed sovereigns, not banks, for the equivalent “core-in-periphery” crisis. Yet the cause is the same, and as this chart shows, even the timing is the same.

And yet….Greece does have a competitiveness problem. In this Hausman is correct. But the question we should be asking is why Greece’s competitiveness declined so much in the 1990s, why it started to improve in the 2000s prior to the development of the “core-in-periphery” leveraging flow system, and what can be done now to restore it. Greece’s public finances are a red herring.