Better-Than-Expected Figures End Six Years of Contraction

The figures were better than expectations—making Greece one of the fastest-growing economies in the eurozone—and confirm that a promised recovery is now under way. Economists had forecast between 1% and 1.4% growth compared with a year ago. On a seasonally adjusted basis, Greece’s GDP rose 0.7% quarter-on-quarter.

Output was also revised higher for the first six months as part of Europe-wide changes to GDP estimates. They showed that Greece technically emerged from recession in the second quarter when the economy grew 0.4%. The latest figures confirm that Greece is now on track to record its first full year of growth in more than half a decade this year.“Taking into account the average growth rate for the past nine months, the economy is on track to reach its 0.6% full year target,” said Nikos Magginas, a senior economist at National Bank of Greece . “The end of the recession came about mainly from growth in tourism, but private consumption also entered positive territory in the second quarter of the year.”

The last time Greece’s economy was in positive territory, in the first half of 2008, the world financial crisis was still in its infancy and the Greek economy was coming off a decadelong public works and consumer spending fueled boom. All that would change a year later when the country disclosed a yawning budget gap—equal to almost a sixth of GDP—forcing Greece to seek two successive rescue packages worth some €240 billion ($299 billion).

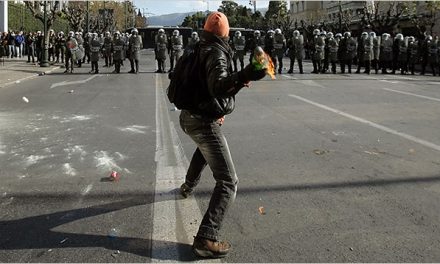

But the country’s international creditors—its fellow eurozone partners and the International Monetary Fund—would demand tough austerity measures in exchange for that aid. Waves of spending cuts and tax hikes, totaling more than €50 billion, sent the economy into a tailspin. In 2011, the year after Greece received its first bailout, output would crash by almost 9%. Greece’s economy is now roughly 30% smaller than it was six years ago.

Despite the encouraging figures, the years of austerity have left deep wounds in the Greek economy that will take a long time to heal. Unemployment, though down from its peak, is still at a staggering 25.9% of the workforce. More than 100,000 businesses have closed, and roughly a quarter of Greek households live close to the poverty line.

Economic confidence, though back to pre-crisis levels, remains fragile. And for most Greeks the statistical growth recorded in the second and third quarters has yet to translate into improved standards of living.

“Growth? What a joke. Every year things just keep getting worse. Talk of growth is funny at first, then you get angry,” said Kosti Sidiropoulos, 45, the owner of a cafe in central Athens.

Mr. Sidiropoulos said that in the five years since the start of the Greek debt crisis, his sales have fallen by more than half, forcing him to lay off seven of his 13 employees and to reduce his opening hours by a third.

“I’m not optimistic. I think that things will continue badly for the next few years and then we will see the economy stabilizing,” he said. “We will have growth when people start smiling again, when there is a positive vibe out there. Right now everyone that comes in here is miserable.”

In the southern city of Kalamata, best known for its olives, local businesses say the economy is bouncing back. But the mood remains cautious, underscoring how delicate Greece’s situation still is: the crisis of the past few years has abated and things have stopped getting worse, but a recovery isn’t being felt.

The continuing credit squeeze, unemployment, an ever-changing tax code, and cutbacks in government services are still challenges, businessmen say.

Coffee merchant Giorgos Spinos, who runs the business started by his grandfather almost 100 years ago, says sales are up nearly a third from their trough and he has recently hired new staff. He has been thinking of moving to larger premises. But for now, he’s staying put, reluctant to invest in new facilities and still uncertain about the future. Despite improved sales, he said a quarter of his customers are late paying—double the number two years ago.

“I am scared. Conditions aren’t stable yet. I believe that things will remain like this for several years,” said Mr. Spinos, 48. “My goal is just to stay alive.”

Those fears have also grown amid fresh concerns over Greece’s volatile political landscape. Early next year, Greece’s government must ask parliament to vote for a new head of state when the current one’s five-year term ends.

The government doesn’t have the supermajority needed to elect a president, and there are growing worries among investors that it may have to face snap elections in the spring. Public opinion polls suggest national elections would likely bring the antiausterity opposition Syriza party to power.

An employee works at a production facility owned by Giorgos Spinos. Unemployment, though down from its peak, is still at a staggering 25.9%.

Since mid-September, Greece’s financial markets have reflected such jitters. The Athens stock exchange has slumped roughly 25% in the last two months, while the yield on Greece’s benchmark 10-year bond has climbed to around 8%, above the level where the country first sought an international bailout.

“Greece will achieve its full-year GDP target, but the problems will emerge again during the fourth quarter of the year, and are expected to remain in 2015 and maybe 2016,” said Panagiotis Petrakis, economics professor at Athens University. “Economic activity is likely to be stressed because of the political uncertainty.”