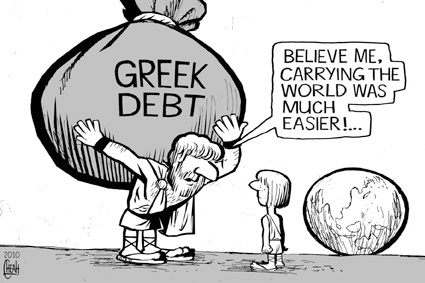

To Aristides Belles, it’s clear what’s blocking Greece’s recovery: a quiet build-up of about 164 billion euros ($208 billion) in private bad debts.

“The inability of Greek companies to repay their loans to banks and their dues to the state is clearly holding back Greece’s return to growth,” said the chief executive officer of Athens-based Nireus Aquaculture SA (NIR), a producer of sea bream, sea bass and processed fish. “It’s more necessary than ever for all parties involved — banks, corporates and the state — to agree on an arrangement.”

As Greece and its euro-area creditors meet tomorrow to review its progress ahead of another round of talks on repayment terms for its public debt, a less-visible crisis is looming on another front: bad debts of households and companies. The borrowings, amounting to about 90 percent of Greece’s gross domestic product, are weighing on the country’s hopes of recovering from the steepest and longest recession on record.

Non-performing loans at Greece’s banks have reached almost 80 billion euros, according to the country’s Growth and Competitiveness Minister Nikolaos Dendias. To top that, Greek households and corporations had overdue taxes of 69.2 billion euros in August, data from the public revenue secretariat show. Also, “collectible” social arrears to pension funds exceed 14.5 billion euros, according to labor ministry figures.

“Some of this debt can never be recovered and should be written off,” said Panos Tsakloglou, a professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business who was Greece’s representative in the working group of senior euro-area finance ministry officials until June.

Debt Forgiveness

Although Finance Minister Gikas Hardouvelis expects Greece to return to growth in the third quarter this year, the bad debt threatens to curb new lending needed to stimulate the economy.

Greek 10-year bond yields rose 12 basis points to 6.28 percent as of 11:09 a.m. in Athens, the biggest increase for sovereign benchmark debt in Europe. The Athens Stock Exchange Index fell 0.1 percent to 1,085,4 at 11:19 a.m. It has fallen 18 percent in the past six-months, the second-worst performer of primary indices tracked by Bloomberg.

Greek lenders have come to terms with the idea of private debt writeoffs. The economy won’t grow unless the debt of companies and individuals is restructured, said Anthimos Thomopoulos, Piraeus Bank SA (TPEIR) CEO, in a Sept. 1 interview.

The restructuring of Greece’s public debt was key to its return from the brink. Following the biggest government bond writedown in history, Greece will pay 4.9 percent of its GDP on average in annual interest payments over the next five years, according to Athens-based Eurobank Ergasias SA. (EUROB)

Turning Sour

That’s less than Italy’s 5.5 percent. Also, Eurobank estimates that the nominal interest rate on Greek debt is lower than that of Spain, Ireland, and Belgium.

“Yes, Greece’s debt to GDP is high, but it’s going to decline,” Finance Minister Hardouvelis said in a Sept. 19 speech in London. “There’s a difference between face value and market value. The market value is low because the duration is high. The average maturity of Greece’s debt is now 16.4 years.”

Greek private debt, without a similar restructuring, has been turning sour.

That’s following a six-year-long recession that wiped out more than a quarter of the national output and left 27 percent of the workforce without jobs.

Recession Effect

“As a secondary effect of the sharp fiscal consolidation, austerity and recession, the number of people and companies that cannot pay their taxes or service their pre-existing loans has multiplied,” said George Pagoulatos, a professor of European politics and economy in Athens.

“You could say that the policies aimed at tackling the large budget deficits and public debt have ended up generating a problem of mounting private debt to GDP,” he said.

The Greek government may need to address the country’s private-debt crisis before it can convince its external lenders to give it additional relief measures.

The government is seeking an early bailout exit after the end of the next compliance review by the troika — the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission and the European Central Bank. It also wants to ask for a further easing of repayment terms on the emergency loans it received from the euro-area crisis fund.

Growth Overhang

Before getting there, however, it needs to convince the bodies that it is complying with commitments — one of them being effectively dealing with bad private debt.

“Unless resolved upfront, this overhang of debt will dampen growth,” the IMF said in its latest review of the Greek adjustment program. “For, unlike others, Greece does not have the luxury of waiting for growth to lift the overhang.”

A finance ministry official said that the government hasn’t decided yet whether a bill due to be submitted to parliament later this autumn will be designed to provide a framework for the restructuring of bad bank loans only, or will also include provisions for unpaid taxes and social contributions.

This is a subject to talks with the Troika the official said, asking not to be identified, in line with policy.

Meanwhile, Syriza, Greece’s biggest opposition party, has pledged to use 2 billion euros from the budget in partial debt forgiveness measures. Its leader, Alexis Tsipras, also said that he expects a positive fiscal impact from easing servicing terms on unpaid taxes. Greek Minister Dendias mocked the pledges, saying they’re negligible relative to the scale of the problem.

For Nireus Aquaculture’s Belles, the delay in dealing with the issue just exacerbates the asphyxiation of the economy.

“Banks are unable to use their basic tools, like, for example, a haircut for viable companies, due to fear of political persecution or legal repercussions, as the existing legal framework can’t cover them,” he said.