In the aftermath of a bitter civil war that had virtually annihilated the left and elevated the right to positions of dominance in the parliament, cabinet, administrative apparatus, armed forces, and police, the Greek electorate handed the center and (to a lesser extent the left) the left a smashing victory, with 63% of the vote. The Populist (led by Tsaldaris), who had won 191 of the 250 seats in 1946, were reduced to 61, while the centrist parties (led by Plastiras , Venizelos and Papandreou captured 133 . In addition the leftist Democratic Front ( led by Sofianopoulos and Svolos) garnered22. According to the agreement by the leaders of the center, published in the press , Plastiras would assume the Post of Prime Minister. To the Greek right, and particularly to the Palace and the officer corps, the prospect of a Plastiras government was particularly galling”.

The interactive intrigue by Americans, the Palace and the Greek right that followed to stop Plastiras by is summarized below to give the reader a fuller appreciation how the Greek electorate were denied their leadership choice.

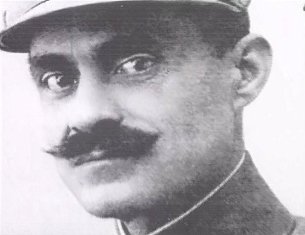

“Naturally U.S. officials had little use for General Nicholas Plastiras, a former Prime Minister who emerged as a prominent advocate of political efforts to end the civil war. In November 1948, a group of Plastiras’ followers sent U.N. President Herbert Evatt a telegram congratulating him for proposing that the civil war be halted by “measures of compromise”. Grady ( Henry F. / U.S.Ambassador), clearly irked by the move, suggested telling Evatt that the Plastiras’ group had “no public following in Greece” and that its “fellow-traveling character” was “becoming even more apparent”. In a more detailed report containing a lengthy memorandum by Plastiras’ followers, Rankin( Karl / USA Charge d’affaires) commented it was “not difficult to understand why the General is popularly believed to have been ‘captured’ by fellow-travelers or why he has largely the prestige which other wise might be accorded him as one of the ‘grand old men’ of Greek politics.” The memorandum expounded, “in but thinly veiled language, the ideas which have become all too familiar from the mouthings of the Communists and other bedfellows.” In June 1949, when Plastiras told the embassy that he would like to visit Washington for conversations with US officials, Grady conceded that the General was not (a) Communist and probably not (a) conscious “fellow-traveler”; nevertheless, “he is extremely politically naive and might be maneuvered into (a) position of front man by fellow-travelers.” Soon afterward, Grady reported that the Greek government had denied Plastiras a passport and expressed its own relief that the general would not “be allowed to wander abroad.” The good news from Grady crossed the telegram of Acting Secretary of State James Webb, who told the ambassador to inform Plastiras’ followers that, despite his “patriotic services to Greece and anti commie record would not be received by high U.S. officials “since US policy aims at avoiding involvement in internal Greek politics.” Having made this ritual bow, Webb added that Plastiras should be urged to join the “united front of all loyal Greeks” in the face {of the} common commie peril.”

The problem with Liberals like Tsouderos, Sofianopoulos, Lambrakis, and Plastiras was not that they were Communists or even “fellow-travelers”; rather they were simply not as anti-Communist as the Americans…

“Although Minor’s (Harold / USA charge d’affaires) dispatch of July 19, 1950 suggested the Korean War as a turning point in the American appraisal of Plastiras, the Embassy had long given disparaging reports to Washington about his potential use by Communists. Indeed Minor had written one such report in December 1949…”