MENAFN – Asia Times)

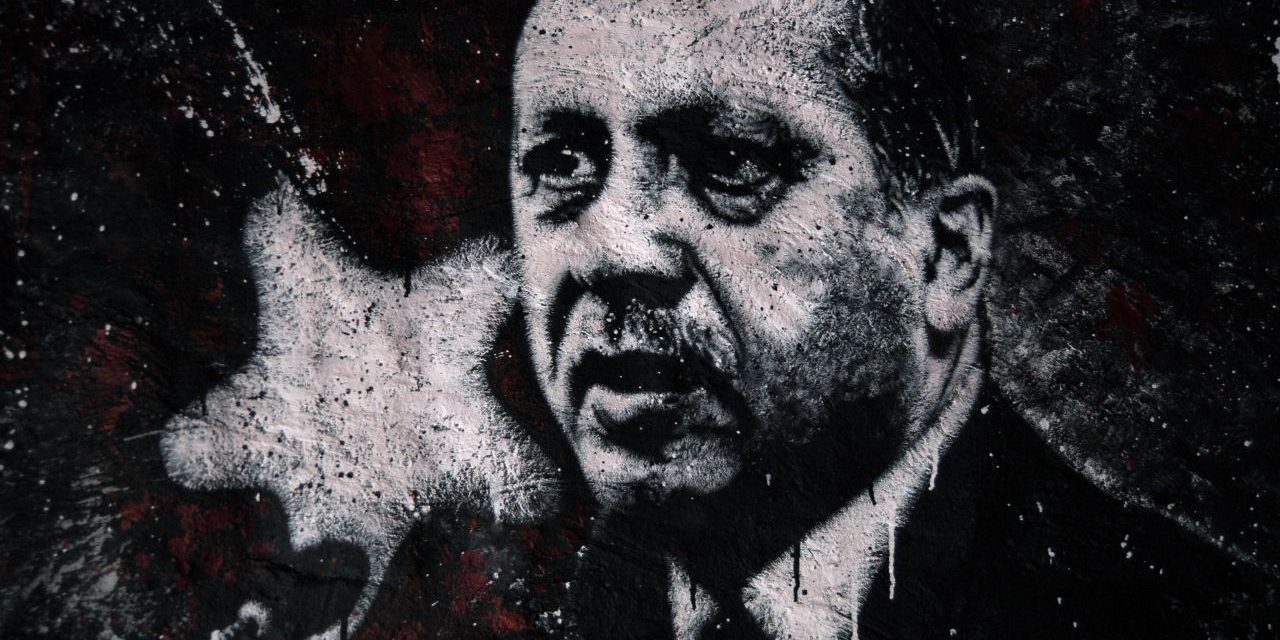

There are many who invested hope in the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan for a comprehensive, viable and lasting solution for the Cyprus Problem. When his Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002 he was seen as the moderate leader who could compromise Kemalism with political Islam and make the necessary reforms that could safeguard the rule of law, bolster individual rights and pave the way for the entry of Turkey to the European Union.

This reasoning was based on the assumption that Turkey, a candidate since 1963 for joining the EU, would see the benefits of a future entry to the European bloc and thus display a more conciliatory approach regarding the Cyprus Problem. At this point we must recall that Greece, an old member of the EU, in 1995 in Helsinki consented that Turkey should be given the chance to be a candidate for accession to the bloc.

The daily<> Must-reads from across Asia – directly to your inbox

However, all these hopes proved fruitless. As Erdogan was overcoming the obstacles in his fight with the deep state and the more he was ensuring his tight grip over the Turkish political system, the more he was becoming totalitarian.

In the domain of external relations he followed a neo-Ottoman foreign policy based on the doctrine of “strategic depth” and “zero problems with Turkey’s neighbors” of his adviser and former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu. However, those two aspects of Turkish foreign policy proved to be irreconcilable and shifted from “zero problems” to ” nothing but problems.” Turkey’s relations with its neighbors Israel, Syria, Armenia and Greece gradually deteriorated.

Focusing on Greco-Turkish relations, Ankara displays a great deal of revisionism. More specifically, Erdogan and other officials question the Treaty of Lausanne, the basic pact that defined Greece’s borders with Turkey as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922.

Ankara questions the sovereignty of many islands in the Aegean Sea, while at the same time it regards as a casus belli the extension of Greek territorial waters from 6 nautical miles to 12. On this point there is a contradiction between Ankara’s words and deeds, since Turkey extended its own territorial waters to 12 nautical miles in the Black Sea. We must bear in mind that Turkey is not a signatory state of the United Nations Convention on the Sea of Law (UNCLOS) of 1982. However, it is bound on the issue by customary international law.

Gas exploration dispute

As regards Cyprus, Ankara supports similar arguments. Turkey, which does not recognize Cyprus’ maritime agreements with its neighbors (Egypt, Israel and Lebanon), has at various times threatened to use force if the Republic of Cyprus does not terminate gas-resource research and drillings. Even worse, in February Turkish warships blocked the gas-exploration activities of Italian oil and gas company Eni (specifically, the drillship SAIPEM 12000) in Block 3 in Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ), claiming that the drilling activities infringed the rights of Turkish Cypriots.

Turkey demands that any new discoveries of natural gas must be equally shared between the two communities in Cyprus. On the other hand, the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus proposes that any newly discovered gas will be shared analogically to the Turkish Cypriots only after the solution of the Cyprus Problem.

Ankara does not recognize the continental shelf of Cyprus, claiming that some Cypriot-claimed petroleum blocks fall in Turkey’s continental shelf. Moreover, in 2011 Turkey signed an agreement with the regime of the occupied territories in Northern Cyprus on continental-shelf delimitation. Currently, Erdogan demands the termination of all gas-exploration activities by the Republic of Cyprus, threatening that Turkey will start its own drilling in Cyprus’ EEZ.

Greco-Turkish relations are at a critical crossroads. The inflammatory rhetoric of the Turkish president and other officials and the continuous violations of the Greek flight information region (FIR) by Turkish warplanes might lead to a ‘mistake’ in the Aegean that could lead to wider escalation.

To this complex political landscape we may add the issue of the two Greek officers being held by the Turkish army since the beginning of March for accidentally crossing the Greek-Turkish border at Evros. Erdogan linked the issue with the fate of eight Turkish officers who requested political asylum in Greece after the failed coup in Turkey of July 2016. Greek authorities strongly reject such an exchange, emphasizing that this cannot take place in a country where the rule of law and the protection of human rights prevail.

Turkey’s actions in the Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ were rebuked by European officials at the EU-Turkey summit in Varna, Bulgaria, on March 26, but the next day Erdogan accused the EU of being biased and warned that Ankara would not retreat from its stance on the gas explorations.

Turkey’s intransigence, though, does not help its quest for accession to the EU, while at the same time it does not create any ground for optimism that the faltered talks for reunification of the island of Cyprus will resume soon.