Global markets were diving Monday morning after Greece closed its banks and appeared increasingly likely to miss a critical debt payment on Tuesday, potentially setting off a default that could lead to the country’s exit from the euro zone. Yet while economists say the Greek crisis would certainly be a roadblock for the U.S. economic recovery and a setback for the global economy, it may not be a disaster unless it sparks a broader panic.

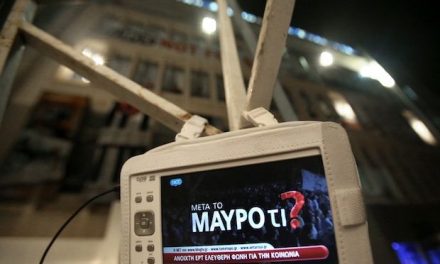

There is no question that the outlook for Greece is grim: The country’s financial system ground to a halt over the weekend as European officials rejected its latest plea for more time to negotiate the painful reforms the Europeans demand in exchange for additional aid. The Greeks have been draining their deposits for weeks, but the breakdown in talks led the European Central Bank to freeze emergency loans to the country’s banks and limit the amount that citizens can withdraw to the equivalent of just $66 a day. Greek officials said banks will be shut down until the country holds a public vote next week on whether to keep working on a deal to pay back its creditors, but Greece is facing an imminent deadline to make a 1.6 billion euro loan payment.

It remains unclear how much the rest of the world will be drawn into this Greek drama. The United States has very little direct exposure to Greece, and investors have had years since the beginnings of this crisis to limit their exposure. The Greek economy is roughly the same size as Connecticut and accounts for less than 1 percent of all U.S. trade — much of it in vegetables.

In the short term, stock and bond markets are likely to be volatile. Asian stock markets fell around 3 percent Monday, while as of 6:50 a.m. EDT, European markets were down almost 4 percent. U.S. futures trading suggested more modest but still significant declines of more than 1 percent Monday.

If the Greek crisis is prolonged, a flight-to-safety in U.S. Treasury bonds could bolster the dollar, crimping exports and economic growth. Speaking at a news conference earlier this month, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen was cautious about the implications of turmoil in Greece for the United States.

“I do see the potential for disruptions that could affect the European economic outlook and global financial markets,” she said. “To the extent that there are impacts on the euro-area economy or on global financial markets, there would undoubtedly be spillovers to the United States that would affect our outlook as well.”

Analysts say the worse things get in Athens, the greater the risk of widespread financial panic.

If Greece defaults on its debts — a scenario that seems highly possible at this point — it could then be forced to leave the European Union and drop the euro, which is used by 19 E.U. members. That could send investors into a frenzy, pulling money out of not only Greece but other fragile economies as well.

A rapid outflow of capital could in turn destabilize countries such as Spain and Italy. If that were to happen, a tidal wave of panic would wash over Europe and spill over into the United States.

Just a week ago, that doomsday scenario seemed remote. Greece had agreed to key concessions on pensions, and European officials seemed cautiously optimistic that a deal could be reached before Tuesday’s payment deadline. Chris Rupkey, managing director at MUFG Union Bank, said the Dow Jones industrial average could fall 2 to 3 percent Monday after the turmoil in Greece escalated this weekend.

Still, he believed that the damage would likely be contained and short-lived.

“We don’t see contagion risks, continued losses that grow over the next week, from the news that has come out so far,” Rupkey wrote in a research note. “We think they have to actually pack their bags and leave the Eurozone to cause more damage to the markets, at least in terms of getting the market’s worst fears realized.”

Through last week, markets have been quiet about the potential for Greece to upend the euro. A June survey by Barclays found that only 23 percent of investors expected Greece would leave the euro zone within the next three months. And even if it did, less than 20 percent thought that it would weigh heavily on the market.

Much of their confidence stems from efforts by European officials to safeguard their union. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi famously vowed to do “whatever it takes” to preserve the currency. Among other measures, the ECB unleashed a massive open-ended stimulus program early this year and could ramp it up if the euro zone begins to falter.

In a statement Sunday, International Monetary Fund Director Christine Lagarde said she was “disappointed” by the stalemate but emphasized that the organization would work to limit any disruptions to Greece’s neighbors.

“The euro area today is in a strong position to respond to developments in a timely and effective manner, as needed,” she said.

The turmoil in Greece comes just as Europe’s economy seemed to be reawakening. Recent data show that the euro-zone economy expanded by 0.4 percent during the first quarter — the fastest rate of growth in about two years. Perhaps most importantly, the recovery seemed to be spreading throughout Europe. France and Italy, two of the region’s largest economies, registered solid growth during the quarter after years of struggling to emerge from the global recession.

Meanwhile, in the United States, many economists have been predicting a stronger second half of the year after the disappointing start. The economy contracted over the winter, and the rebound this spring has been less than robust. But a strengthening housing market and encouraging growth in consumer spending had many hoping that the recovery was finally picking up again.