Which Greek politician will tell Greek voters the truth?

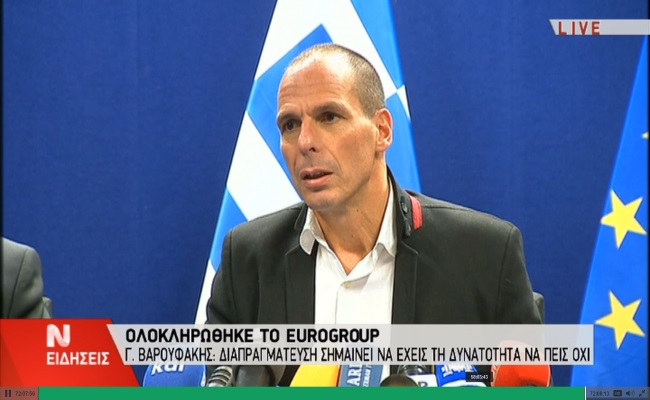

Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis enjoys the limelight — and a bit of controversy. At a conference of free-market economists in Athens on Wednesday, he teased the audience with well-informed references and subtle jokes alluding to libertarian intellectual gurus, such as Friedrich von Hayek and Robert Nozick. To watch the maverick economist poke fun at his hosts was entertaining, and Varoufakis, an articulate and sophisticated thinker, seemed to be having a good time.

In addition to this intellectual sparring, he also conveyed a more serious message. In order for Greece to remain in the eurozone and continue discussions with its partners, there needs to be a shared understanding that Greece cannot — and will not — repay its debt. As a result, the world should stop pretending that the way ahead lies in yet another deficit reduction program orchestrated by the Troika.

Varoufakis’ message resonates. But not all Greeks agree. Miranda Xafa, an economist with extensive experience in the Greek government and International Monetary Fund (IMF), claims that austerity is not the core of the problem. At the present time, she says, the debt service accounts for a mere 3.1 percent of GDP. “The real problem,” according to Xafa, “is that nobody wants to buy Greek goods and services.”

George Bitros, a professor emeritus at Athens University of Economics and Business, agrees. “Between 1954 and 1974, growth rates in Greece exceeded six percent. Have we unlearned how to grow since then?” While much of the West has seen an economic slowdown since the 1970s, Greece has been singularly unsuccessful in adjusting to the new economic reality.

Massive red tape, cronyism, a bloated public sector, and tightly regulated labor markets seem to be the main culprits behind low labor participation rates and high unemployment, particularly among young people (youth unemployment rates now exceed 50 percent). Reforms in these areas are necessary, regardless of what one thinks of the Troika, Angela Merkel, or the prospective cancellation of Greek debt.

Even Varoufakis admits that such reforms are needed: “Without reforms, we will never recover.” But talk is cheap — and unconvincing in light of Syriza’s political platform and the current government’s track record.

Greece’s fiscal problem, in turn, is driven primarily by welfare spending, which accounts for 42 percent of total government expenditure, according to Aristides Hatzis, a well-known free-market academic, educated at the University of Chicago.

Of course, welfare spending is not bad per se. In fact, it would be sensible to have a strong safety net if the government were to put in place structural reforms that may hurt the poor. But the Greek welfare state is largely a handout for the rich. “In 2011, the top income quintile received more than three times as much in social benefits than the bottom quintile,” explained Mr. Hatzis.

Many Greeks agree that the real problem is political, not economic. “No politician will ever dare to do what is needed,” a Greek friend told me. Another one, a former government official, thinks that “the difference between the successful reformers of Eastern Europe and Greece is that in Eastern Europe, people were dissatisfied with the status quo. In Greece, everybody just wants to go back to how things were before 2010.”

That is not possible, obviously. But reality does not seem to constrain political debate in Greece these days. Recently, the government suggested that Germany owes Greece €279bn in World War II reparations. Brushing aside the myriad of troubles with such a calculation, to even hint that any fraction of the money will ever reach Greece is a disingenuous distraction from the failure of Greece’s political elites to adopt effective reforms.

Kyriakos Mitsotakis, of Greece’s center-right New Democracy party — and son of the former Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis, exiled after the military coup in 1967 — says that the first responsibility of political leaders is to tell people the truth. Neither the current nor the former government have done that. “The whole divide between the supporters and opponents of the memorandum with the Troika was artificial. The genuine problem was that we were bankrupt.”

In part, Syriza’s rise to political prominence can be explained by the unwillingness of Greece’s politicians to convey this simple fact to voters. But it was also driven by the catastrophic failure of policies adopted after 2010. Instead of serious, durable, reforms of the kind pursued in Latvia or Estonia, Greece’s fiscal consolidation was focused on squeezing additional revenue from a very small base of tax-compliant ‘suckers,’ as one Greek put it, without any effort to make the economy more flexible or generate private-sector opportunities.

Sadly, the ailing economy might just herald bigger troubles ahead. Golden Dawn, Greece’s neo-Nazi party, has benefited tremendously from the crisis, as has the Kremlin, which has gained a new ally inside the EU and NATO. Greece is also falling behind on numerous other metrics, including volunteering and organ donation, suggesting a slow erosion of the country’s social capital and trust.

While late, it is possible to change course. But that will require more than just Varoufakis’ intellectual panache and charisma. It will require the maturity, resolve, and courage to tell Greek voters the truth — and to do the right thing for their country.

Dalibor Rohac is a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.