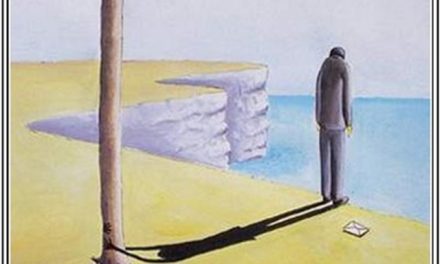

Greece’s financial crisis is also a human one. The government is unable not only to collect taxes and manage its debt, but also to assist those whom the crisis hit hardest.

It’s just after 7pm, still daylight at the Propylaea, the gateway to Athens University on Panepistimiou Street, right in the city center. The passing crowds barely even give the now totally motionless man a second glance. A gaggle of teenagers sits laughing on one of the benches opposite him, also unperturbed by the sight — they’ve grown up with it, just another part of life in crisis-hit Greece.

Widescale, and overt, use of drugs is just one of the many signs of societal degeneration readily apparent in Greece since the global crisis hit. The country’s GDP has fallen by more than €88 billion since 2009. As Europe obsesses with the far-left Syriza government’s battle with the EU and the IMF over austerity measures and bailout funds, it’s easy to forget that Greece’s financial crisis is also a human one.

On a bright May afternoon, I went to see Ekavi Valleras to try to understand the scale of the problem. She is a director of Desmos, a non-profit foundation that secures donations and pro bono services from the private sector to support organizations working to help those that the crisis has hit hardest. Desmos does everything from supplying pasta and toys for front-line NGOs to distribute to those in need, to providing Internet and phone lines that allow the service providers to function. Desmos’s help is badly needed. Valleras returned to Greece after living in London and New York, where she worked for two years for the Global Philanthropy Department and the Merrill Lynch Foundation. She and some colleagues founded the organization in January 2012; since then, it has given out goods and services worth more than €1.5 million.

Valleras has no doubt that Greece is experiencing a serious humanitarian crisis. “The general consensus of NGOs active in social work is that there has been a sharp increase in the number of people failing to address their monthly basic needs,” she said. “This has come from increased unemployment and a reduction of benefits. Households that once had two working parents and minors now have no working parents.”

Greece has both the highest overall unemployment rate in Europe, at 25.7 percent, and also the highest youth (defined as anyone under the age of 25) unemployment rate, at 50.1 percent. But nothing better illustrates the gravity of the situation than learning what Greece’s newly-minted poor lack the most: food — in an EU country in 2015.

“And it’s the hardest to come by as well,” Valleras explained. “There are only a handful of food manufacturing companies in Greece, and nutritional products are needed everywhere.” People are struggling to cover their basic needs in almost all respects. “After food, personal hygiene products are most needed,” she said.

Fuel for heating schools

Over the last three winters Desmos has distributed 171,000 liters of heating oil and 9.9 tonnes of pellets (a type of fuel made from processed wood chips) throughout Greece. The fuel goes to heat schools, homeless shelters, orphanages — everywhere the crisis threatens the most vulnerable.

I asked Valleras if the government is doing enough to help the Greek people. “What groups like ours do is an emergency relief effort,” she replied. “Long-term planning needs to be made, and this must be done at the state level. So far I don’t see any progress. The government’s primary concern is the financial crisis, not the humanitarian crisis. Building social networks requires money and that isn’t there.”

Little is being done at the international level. In March, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker pledged €2 billion for what he described as Greece’s “humanitarian crisis,” but said, somewhat vaguely, that the money would be spent on growth and “social cohesion.” That sum is miniscule compared to the money that has been lent to Greece so that it can repay its creditors.

I wanted to see firsthand how the crisis was devastating this country, so I arranged to meet Maria Karra, one of the founders of Emfasis, a non-profit organization that works to combat the effects of the crisis on the frontline of Athens’ streets.

Emfasis was set up in 2013 with the goal of directly engaging with Greek society’s most vulnerable people — many of whom now have been made homeless by the crisis. Maria and her team use a white van emblazoned with the Emfasis logo to navigate the city and she agreed to let me ride along with them for a day.

After a brief meeting in her office, a private house on a quiet street, stocked with supplies from cooking oil to diapers, the first stop is the Emfasis Social Support Corner, the group’s “street office,” a space given to them by the Athens local authorities in Synathina, opposite the city’s central market. Here, two trained social workers, Ioanna Panagopoulou and Panayiota Tzaroucha, hand out food and drink to vulnerable people while providing everything from information on government benefits to help with resumes for job applications.

As we mill about in the street outside the office, a homeless man with red sores across his face approaches Karra and asks her for a blanket. She tells him to have a seat on some nearby steps while she speaks to the volunteers. I cross the road to buy some water at a local kiosk. When I return, some volunteers are handing the man a red blanket with a yellow pattern. He ambles off contentedly.

“Fast service,” I said to Karra.

“That’s what Greece needs,” she replied.

***

I asked Karra if the crisis was getting better or worse. “I can only talk about what I see,” she replied. “And we have seen a huge increase in the numbers of homeless and drug users on the streets.”

More worryingly, the group has noticed an increase in homelessness among people of what it terms “productive ages.” From a sample of 750 detailed case studies of street sleepers, Emfasis discovered that in 2014 the average age of homeless people in Athens was 45 and older. This year the average age has dropped to 35 and over — typically a person’s most productive working years.

Why the drop in age? “It’s a domino effect,” she replied. “The people with higher tax obligations, the ones with the greatest financial overstretch like mortgages were the first to suffer. They were encouraged to take mortgages and consumer debt. It was Fannie Mae in microcosm. They were usually older and often well-paid so they could be sacked and replaced with several younger employees on far lower salaries. But now the problems have worked their way down the system to the younger people living in rented accommodation. It’s really bad now.”

No one knows how many people have been made homeless by the crisis. As we drive off to another appointment Karra points out that the problem is not limited to those living on the streets. Many are staying with relatives, or sleeping in their cars or work spaces. According to the EU’s Federation of National Homelessness Organizations, as many as 15,000 people can be classified as homeless in Athens alone. Most are men, and around 60 percent have substance abuse problems.

And half of them are non-Greek. As the central axis in what is described as the “Anatolian geopolitical corridor,” Greece is a key entry point into Europe for (often illegal) Middle Eastern, Asian and African migrants, who have also suffered, facing a vicious combination of poverty and racism. It’s almost impossible to accurately estimate the number of illegals in Greece, but in 2014 alone, 77,163 foreign nationals were arrested for illegal entry and/or illegal stay. From 2007 to November 2014, 785,000 people were arrested for not having the proper residence permits. All this in a country of just 11 million people.

As we drive deeper into downtown Athens, the buildings become more dilapidated; the Greek lettering on signs morphs into Pashtun, Urdu and Arabic. We arrive at a small patch of park in a poor neighborhood that Karra asks I don’t mention by name, where Emfasis volunteers are working with a group of migrant children. Emily Kallitsounaki and Zetta Stametopoulou, both of whom have training in psychology, are talking to five street kids, from the age of around four to 12. They get them to line up and hold hands. The children laugh and cheer.

“They are teaching them to be more disciplined and to manage their aggression,” Karra explained. “This is a big problem as they are often forced to fight for their begging spots on street corners or at traffic lights.”

“Every Christmas, we try to do something for the kids and ask them to draw up a list of gifts they would like. Last year, the overwhelming request was for wings: so they could fly away from here.”

***

As the sun sets, I walk through central Athens with Karra and her team: Orestes Makris, Iro Ntrouva and Lida Tzialla, the latter a young woman who cares for children with special needs during the day before volunteering with Emfasis in the evenings. I remark to Karra that almost all the volunteers I have seen are women. “It’s true, 80 percent of our volunteers are female.”

“Men are full of enthusiasm at the start, but they lack the mileage.”

Night is when crisis Greece fully emerges. As we continue walking Karra points out all the homeless people setting up for the night. It’s as if the fabric of the city is re-forming before our eyes. Shop doorways become temporary bedrooms as sleeping bags are laid out, surrounded by plastic bags containing clothes and shoes. Outside the entrance to a church, an elderly man has built his own enclave beneath its overhanging roof. Cardboard boxes surround his makeshift bed, several plastic water bottles are scattered around him.

At night, Emfasis ventures further into Athens’ worst neighborhoods and by just after 10pm, I am sitting in the back of the van surrounded by meals donated by a local supermarket and hot flasks of tea as Karra and one of the Emfasis co-founders, Solonas, drive through empty streets. The van is vital because it gives the group greater mobility and because it provides protection: it is a place to run to if things get violent.

After several stops to deliver the food and drink we head into Metaxourgio, a down-at-heels neighborhood north of the city center. By an overpass I meet Vassilis, a homeless man in his fifties. Sitting on a curved concrete bench next to a shopping cart filled with his belongings, he gives me his take on the crisis. “The social system here is made in such a way that if you have one misfortune it doesn’t help you, it just condemns you.”

“I’m not optimistic at all. Everywhere I see the same story repeat itself. Everything starts and ends with politicians. If they wanted to solve the problems they would. I don’t believe in austerity. It protects the people who have money while everyone else suffers. It’s a lie.”

The same repeating story

A while later, Karra and I meet Dmitris, an older man swaying erratically on a bench outside a church. He is clearly on drugs but is reasonably articulate. His problems, he tells me, began in 2008, just as the crisis hit. He used to be a sound engineer working all over the world. He was all set to sign a big contract but it was cancelled at the last minute.

“Back in the day I would earn 130,000 drachmas [around €2,000] for just a few hours work,” he said. “Now I would struggle to work twice a week, and the pay would be ridiculously low. Job opportunities in Greece are next to zero, even for someone like me who went to a proper college for sound engineering. All the young people have run away.”

Dmitris blames the crisis on too much easy credit, which encouraged people to go into debt. “Even the famous singers I worked with were doing it,” he said. “We used to joke: you’re going on a summer holiday? Get a mortgage. You’re having a wedding? Get a mortgage.”

Now Dmitris survives by doing odd jobs. He is afraid of getting back into sound engineering because he fears that he won’t get paid, a common problem in Greece these days. He also fears hanging out with the music crowd and getting back into drugs and alcohol. His plan is to scrape by until he is eligible for a pension at 65. He is 54.

We finish our deliveries in the early hours. As the van drives back through the streets, I see prostitutes standing on street corners and yet more old men and women sleeping rough, and I wonder what happened to the Athens of my youth.