On TV, in museums, on the stage – Hellenic culture is all the rage because it still speaks to us, says Boyd Tonkin. And far from being exclusive or historical, it lies at the heart of modern Western values, showing to us ‘our best selves’

By Boyd Tonkin, The Independent

A few weeks ago, the poet and playwright Tony Harrison received the David Cohen Prize, given for a lifetime’s achievement in literature. Harrison – a working-class lad from Beeston – explained in an inspirational acceptance speech how, as a schoolboy, he would go off to see his favourite northern comics at the Leeds Empire. In his pocket nestled his grammar-school homework of classic Greek plays.

He would use the demotic words he heard on stage “to unlock the tragic texts I had to study”. Much later, he had a dream that those comics had turned up to join the chorus of his masked version of the Oresteia of Aeschylus, in Peter Hall’s renowned production for the National Theatre. That wise-cracking legion of ghosts had come to help him to liberate “the gravitas of Aeschylus, using the so-called ‘low’ art to unlock the so-called ‘high'”.

In 1821, Percy Bysshe Shelley argued – in the preface to his play Hellas – that “we are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their root in Greece.” Ever since, scholars have quibbled about who “we” are and who indeed those “Greeks” may have been. Yet Harrison’s testimony, by no means unique, shows how a culture that peaked 2,400 years ago can still shake and shape the lives of people from outside any narrow elite.

Refreshed by translators as bold as Harrison himself, the drama of classical Athens still packs theatres across the world. In around 441BC, the playwright Sophocles won acclaim for his Antigone, in which the heroine flouts the dictates of the Theban tyrant Creon in order to honour her dead brother Polynices with a decent burial. With Juliette Binoche as its star, Ivo van Hove’s production closes in London this week after a sell-out run and then tours around Europe. If you missed it, in the poet Anne Carson’s striking version, don’t worry. BBC4 has filmed it for a Greek-themed series entitled The Age of Heroes. Other highlights will include an investigation into the life and poetry of Sappho by Margaret Mountford, formerly of The Apprentice, who has a PhD in papyrology.

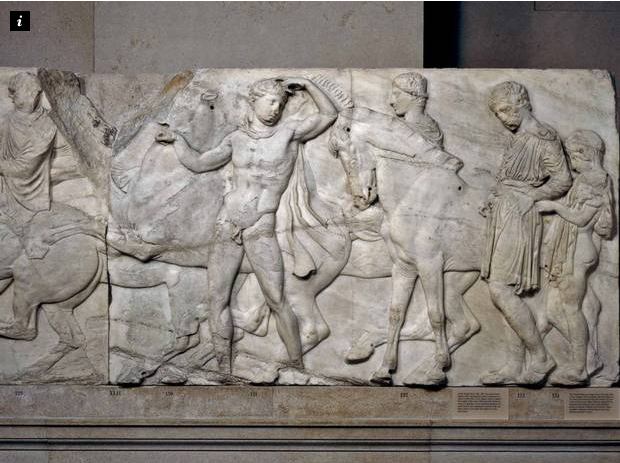

Tomorrow, the British Museum joins the Greek spring chorus with a new exhibition, Defining Beauty, devoted to the body in ancient Greek art. “I hope I don’t come across as a blind Hellenist,” says Dr Ian Jenkins, the senior curator of the museum’s Greek collections, as we sit in the pre-opening hush surrounded by the moulded and chiselled heroes, athletes, gods and monsters of two millennia and more ago. He points out that the exhibition, in common with so much recent research, acknowledges Greek culture’s links with the Near East, Egypt, Persia, even India. Nonetheless, Jenkins is still “not beyond saying that the Greeks invented us. They invented the modern idea of us as human beings with a material and spiritual presence in the world that was individual and unique.” Socrates, the subversive questioner put to a hemlock-speeded death by an Athenian court in 399BC, had first insisted on a “personal moral responsibility for your own soul”. For Jenkins, “democracy lies behind that. And democracy breeds humanism, which breeds increasing realism in art.”

No serious classicist now plants Greek civilisation on a wholly isolated pedestal. Paul Cartledge, an emeritus professor of Greek culture at Cambridge University, underlines that “we are now more sensitive to other cultures in general. We don’t any longer talk about a single thread of lineage from antiquity to the present.” All the same, Jenkins insists that “because Greek art is manifestly so accomplished, it’s difficult to displace it”.

The “universality” so often claimed for ancient Greece need not mean a cold and lofty eminence to which lesser breeds can but aspire. For Jenkins, “I think of the Greeks not as exclusive but as inclusive – as our own best selves”. He stresses that “we humans are at the centre of the Greek universe. They are an anthropocentric tradition in the way that the great religions are not.” Their gods may be formidable, such as the little pocket-rocket of a bronze Zeus from Hungary that Jenkins especially adores; they may be hauntingly, mysteriously lovely, such as the stunning Aphrodite – “Lely’s Venus” – which greets visitors to Defining Beauty. But the Greeks imagined their gods “in the image of mankind”, not as fearsome, nebulous abstractions.

Our best selves. As we grasp in finer detail how the rivalrous seafaring states of Greece negotiated with societies to their east and south, no longer do these divinely gorgeous beings sit snobbily atop what Jenkins calls “some invidious and outrageous pile of cultures”. Neil MacGregor, the director of the British Museum, puts it pithily in the exhibition catalogue. “Greece did not so much go down” – since the Victorian heyday of Hellenic supremacism – “as everything else came up.”

As “everything else” secures a modicum of the dignity and respect always accorded to ancient Greece, the latter’s legacy will change. Meanings mutate across place and time. Paul Cartledge warns that, with Greek as with other history, “the present is constantly changing the past”. Take Sophocles’ Antigone itself. Does the arch-disciplinarian Creon, with his hard-headed insistence on civic law and order against family piety, have an arguable case? Countless readers have thought so – and many male spectators in the Athens of 441BC may have thought the heroine a stupidly headstrong slip of a girl.

When German nationalism was taking root in the 19th century, the philosopher Hegel treated the play as the epitome of a tragic collision not between right and wrong, but between right and right. In February 1944, German-occupied Paris saw the curtain rise on Jean Anouilh’s version of Antigone. Why had the Nazis licensed it, when their accomplices also refused burial to slain Resistance fighters? Because Anouilh’s Creon speaks up for authority and its duties against the luxury of individual protest. His tough measures have steadied the ship of state. No posturing dissident has the right to sink it. “It is easy to say no. To say yes, you have to sweat and roll up your sleeves, and plunge both hands into life.”

If the 20th century saw Antigone as a paradigmatic clash between order and freedom, then the 21st might view it through another lens. Ruth Padel, the poet and classicist, thinks that the core idea of “pollution” in classical tragedy now resonates with renewed force. In Antigone, unburied Polynices will taint the city both physically and spiritually. Sophocles’ Oedipus the King begins “with a plague and a pollution”. No longer do such beliefs belong solely in the domain of anthropology. On our ravaged planet, says Padel, “we’ve got such a strong sense of that we have befouled our ecosystem… that it’s our fault, and that nemesis will follow”. Paul Cartledge, though “not myself a Gaia person”, agrees that an ecologically steered reading of the play could chime with a modern “view of the world as regulated by something above human needs and actions”.

For Padel, the Greek vision of unity, balance and proportion – in the body, the mind, and in society – may still console us too. “The Greeks are about harmony; about fitting together. And we’re now in a time when so much of life seems catastrophic and frightening.” There’s nothing new in this: over the centuries since the Renaissance, and above all since the Enlightenment, the West has gone Greek to understand itself. “As soon as we’re conscious that our age is different,” says Padel, “then we look to the Greeks. They are the first mirror.”

Not everyone has found themselves reflected in that mirror. Post-war scholarship has shone a belated spotlight on the bodies, minds and groups excluded from the ideal realm of those exquisitely fashioned, godlike statues. Paul Cartledge refuses to gloss over the “sexism and ethnocentrism – a polite word for racism” of ancient Greece. “Aristotle on women,” for example, “is very difficult indeed to read… His views are extremely reactionary.” Meanwhile, those beautiful bodies in the British Museum remind us of the Greek cult of flawless youth. To Cartledge, “the ancients have some responsibility” for the time-defying neuroses of the contemporary catwalk, the fashion shoot or the gym. “Old age really was abhorred: physical decay was not something the ancients were keen on – they were the ‘forever young’ fanatics.”

So scholars began to correct the biases of classical tradition. Madness and unreason claimed a central place on the Greek scene, in the wake of ER Dodds’s influential study of The Greeks and the Irrational. Ian Jenkins, however, thinks that the cliché of cool Athenian reason never had much validity anyway: “What do you mean by rational? What is so rational about slaughtering a hundred cattle as a sacrifice to the gods? Why set up this straw man?”

Historians also sought to uncover the experience of the slaves whose thankless toil supported civic democracy in Athens and military might in Sparta. Women, silent in politics but resoundingly audible in drama (as anyone who remembers the sex-strike in the Lysistrata by Aristophanes will know), at last claimed a place at the top table of classical scholarship. We now know more about the female sphere in which, for instance, Sappho lived, beyond the erotic shards of her verse that strike like thunderbolts across two and a half millennia. Thus, as she looks at a beloved woman talking to a man, “tongue breaks and thin fire is racing under skin, and in eyes no sight and drumming fills ears… and cold sweat holds me and shaking grips me all, greener than grass I am and dead – or almost I seem to me” (Fragment 31, translated by Anne Carson).

Elsewhere, in his ultra-controversial Black Athena project, Martin Bernal argued that European classicism had obscured the African roots of much Greek achievement (the British Museum show has some fascinating ceramic depictions of sub-Saharan Africans). And Greek homosexuality, a topic often overshadowed by an Olympic-sized mountain of myth, has come into clearer focus. Ian Jenkins emphasises that the beautiful youths of Greek sculpture served as types of virtue more than as objects of desire; they were not meant to arouse. Near where we talk stands the so-called “Westmacott Youth”, a marble model of the kind of unselfconscious grace that Socrates praised in Plato’s dialogue Charmides.

“This is not a sexual image,” Jenkins insists. “He is not provoking any of the attention he receives.” He is, however, proudly nude. “That is in some way the most important message of the exhibition.” Unlike neighbouring societies, such as Persia or Assyria, for whom the naked body signified defeat and abjection, “the Greeks took nudity as a sign of heroic status or circumstance. Nudity was the uniform of the righteous. It is the aesthetics of ‘kalos kai agathos’ – like the youth there, fair of face and sound of heart.”

For Ruth Padel, the younger generation of classicists has grown up immersed in these debates about class and gender, ethnicity and sexuality, and “now takes all that for granted”. In her recent book Introducing the Ancient Greeks, Edith Hall – a professor of classics at King’s College London – rebuts the sceptics who deploy revisionist research to brand enthusiasm for the Greeks as a mere ancestor-cult of the “Oldest Dead White European Males”. For her, a “constant engagement with the ancient Greeks… has made me more, rather than less, convinced that they evinced a cluster of brilliant qualities that are difficult to identify in combination and in such concentration elsewhere”. To Hall, you hardly need to be a snob or a colonialist to register this special radiance of a people who took up “the human baton of intellectual progress for several hundred years”.

Paul Cartledge declines to sanitise the routine prejudices and inequalities that much Greek culture shared with its ancient counterparts. Still, what inspires him is that “there are always some who are willing to put forward very progressive, non-traditional views” – such as his hero, the endlessly curious, open-minded historian Herodotus. Indeed, the principle of critical debate itself – free, open, competitive and, as Cartledge says, “hopefully backed by logic”– endures as the chief intellectual legacy of Athens above all.

Anyone tempted to turn off and abstain in May’s general election should consult Pericles’ famed funeral oration from 431BC. However much breached in Athenian practice, it still reads as a peerless manifesto for a free society. To Pericles, mourning the dead after a bad first year of war against the Spartans, “our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people… We are free and tolerant in our private lives; but in public affairs we keep to the law.” Above all: “This is a peculiarity of ours: we do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all.” At the very least, go Greek and vote on 7 May.

‘Defining Beauty: the body in ancient Greek art’ is at the British Museum, London WC1, from 26 March to 5 July. ‘The Age of Heroes’ will screen on BBC4 later in the spring. Edith Hall’s ‘Introducing the Ancient Greeks’ is published by Bodley Head