From opposition to the military junta to imprisonment on a desert island and smuggling his films to France. Pantelis Vougaris, one of Greece’s greatest directors, tells of his life’s work: chronicling his country’s cultural, political and social issues.By

Uri Klein, Haaretz

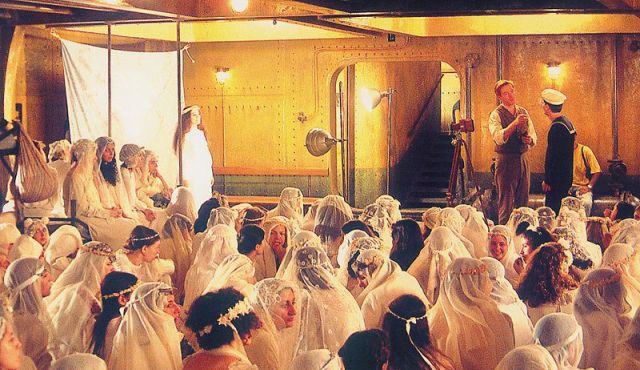

Pantelis Voulgaris, one of Greece’s leading directors, describes his films as journeys. And in fact most of them are journeys to Greece’s 20th century history – whether it’s the 2004 film “Brides,” which takes place entirely on a ship transporting 700 brides “for sale” from Greece to America in the early 1920s; “Deep Soul,” from 2009, which takes place during the civil war in Macedonia in 1949; or “Stone Years,” from 1985, which tells the story of a family from the period of the civil war until the collapse of military rule, and in my opinion is still one of his best films.

Last week the cinematheques in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem screened six of Voulgaris’ films, and on the final day of the event – which was organized by the Greek embassy – the director came to Israel. I met with him for a conversation at the embassy, with Greek ambassador to Israel Spiros Lampridis serving as our translator.

Voulgaris was born in Athens in 1940, and has been fascinated by cinema since his youth. The thought of being an actor passed through his mind, he said, but it embarrassed him and he decided to make films instead. He registered to study in the only film school existing in Greece in the 1950s, and did his practical studies in the only production company.

There he learned to do every task connected to filmmaking, from carrying the camera to being assistant director, a position he filled in over 40 films.

And if he grew up on classic American cinema and particularly liked historical spectacles such as “Ben-Hur,” as he grew up and became more familiar with cinema he was drawn to the neorealistic film that developed in Italy after World War II and dealt with social issues through human-interest stories.

“The members of my generation who wanted to make films were influenced mainly by the neorealistic cinema or the French New Wave,” says Voulgaris, who has a kind and very expressive face. “I always felt closer to the former than to the latter.”

But there was another source of inspiration that honed his artistic sensitivity: His father was one of the most famous church singers in Athens. Through him he discovered not only church music but music in general, which continues to influence him when he designs the structure and pace of his films.

In the 1960s he directed two short films, and in 1974 his firm full-length feature, “The Engagement of Anna,” which told the story of a bourgeois family looking for a husband for their maid, but is afraid that if she does marry, the family will lose her. The film is full of irony, directed at the supposedly good intentions of the bourgeoisie toward the working class. In this film, says Voulgaris, he made considerable use of his memories of the life of the bourgeois family in which he grew up.

When you were planning your career as a filmmaker did you already think you would deal with subjects connected to Greek history and society?

Voulgaris: “Not really. To a great extent it was history that guided me. Until the fall of the military junta in Greece in 1947 you couldn’t make films dealing with the history of the country or criticizing its society. Filmmaking was subject to draconian censorship. Only in 1974 did it become possible, only then could I present to the Greek public questions that preoccupied me regarding the history of Greece and its social structure.

“‘Happy Day’ was my first film that dealt directly with political issues – the exile of political prisoners during the period of military rule, a subject that I researched in depth. Of course, in making the film I also used my personal experience, because I too was exiled to a desert island for about a year and a half toward the end of the military rule.

“I definitely feel that a film director has the obligation to deal with historical, political and social issues, to convey a message and fill the existing vacuum, for example on television and in the school system, which refrain from dealing with these issues. It’s important to me that my films obligate the audience to look back to the past of their homeland. After the screening of ‘Stone Years,’ for example, one of the largest dailies in Greece published a list of 25 recommended books about the civil war.

“And in other cases, after my film was screened in a school or at a university, students approached me and asked where they could find additional information about the civil war or the exile of people during military rule, because they had no additional sources of information. Since I’m not a political leader, a teacher or a priest, the fact that the messages in my films caused the audience to respond and want to know more gave me great satisfaction.

“I deal with historical issues in many of my films for two reasons: First, because we’re a small country with a charged history, and this history has had a very strong effect on the lives of the people. And second, since this history is so charged, it has given rise to many human-interest stories that I’m interested in handling artistically. In Greece, as in Israel, politics is ever-present. Politics is part of everyday life.

“Sometimes I begin to research a chapter in Greek history without being certain that a film will result. I do that because the questions aroused by the historical chapter relate to me – mainly the civil war, which claimed two victims from my family. When I deal with a historical chapter, it’s important to me to be as fair and objective as possible. To be accurate. When I do research I also examine the smallest details, including which films were being shown at the time and what the restaurants were serving.

“When I did my film on the civil war, for example, I found authentic army uniforms from the period. But then I discovered that they were too small for most of the actors, because the Greeks were skinnier at the time due to poverty and hunger. Because I didn’t want to give up on the uniforms I looked for actors who were the right size. But the greatest difficulty in making a historical film is to get the actors to feel that they’re part of the period being portrayed.”

Why were you exiled in 1973?

“At the time I was teaching in what was still the only film school in Greece. The junta sent spies everywhere, and they reported that I was teaching subversive values and also reported, incorrectly, that without permission I had filmed the student rebellion that erupted in the school and signaled the beginning of the fall of military rule.

“Prior to my arrest I really had filmed secretly. I walked around with a camera and filmed images from the everyday life of the Greeks. Had they caught me I would have been arrested immediately. I was able to smuggle those materials to France, and they reached the hands of the French director Chris Marker. He sent me a 16 mm. camera and told me that he needed more of those materials.

“In order to avoid arrest I started a fictitious production company that specialized in films about Greek lore, which was legal, and when a policeman stopped me on the street I explained to him what the company supposedly did, and he released me. From the materials that I had filmed, and reached France, they assembled a 20-minute film that was used as a protest against the military government.

“I was sent to an arid island called Gyaros ,which had a prison built during the civil war. The prison had been closed but was reopened when the junta came to power. At first there were 7,000 political prisoners, but because it was an island and there was no way of leaving, they allowed us to wander around during the day. Years later I was stopped in the street by a silver-haired man whom I didn’t recognize. He praised my film and said: ‘You don’t remember me, but I was the one who arrested you.’”

How did Martin Scorsese get involved in producing the film “Brides”? We’ve seen many films about the immigration of Italians, Irishmen and Jews to America, but very few about immigration from Greece.

“I met Scorsese thanks to my long friendship with the director Elia Kazan. Kazan, who in 1963 directed ‘America, America,’ one of the only films that did deal with the immigration of a young man of Greek descent, told Scorsese about me. Scorsese watched several of my films, and when we met he expressed his admiration and asked me questions about certain scenes. He knew about the massive immigration from Greece to America in the 1920s, and was also familiar with Greek history, so that when we met he already had the idea that I should make a film about that period in Greek history.

“The idea for the film came to me when I was in New York and saw an ad in a museum that was published in The New York Times in the 1920s inviting Greek women to immigrate to America. Then I said to my wife (the admired Greek writer Ioanna Karistiani), ‘What do you think about making a film about that, which will take place entirely on a ship?’ The idea made waves in Scorsese’s production office and Ioanna wrote the script.”

Women play a central role in many of your films. Is that deliberate?

“No, I don’t do it deliberately, but Greek history and society don’t only fill the traditional roles of lover, wife and mother; often they served as the motivating force, and when I write and direct, almost without my being aware of it the female characters become increasingly central to the plots.”

Toward the end of our conversation I ask Voulgaris about present-day Greece, which is suffering from economic ruin, and about the neo-Nazi party, the Golden Dawn. Voulgaris, who perhaps feels that he has already done his part, implies that the question should be directed to the younger generation of film directors in Greece, who want to cut the umbilical cord that connects them to more veteran directors like him and Theo Angelopoulos. They’re very promising directors, he says, very active, and they discuss these issues with realistic determination.