By Sibel Hurtas, Al-Monitor

The most controversial results in Turkey’s June 24 elections came from the predominantly Kurdish provinces in the country’s southeast. The Nationalist Action Party (MHP), whose hard-line nationalist rhetoric hardly appeals to the Kurds, saw a three-fold increase in its votes in the region, while the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the torchbearer of the Kurdish political movement, suffered a decline.

Given the diametrically opposed policies of the two parties, many analysts agree that swing votes and internal dynamics cannot explain the phenomenon. Hence, the MHP’s gains and the HDP’s decline require separate analyses.

Examples of how MHP votes increased from the November 2015 elections include the following provinces: Van (from 6,348 to 16,240), Mus (from 2,708 to 7,051), Diyarbakir (from 6,619 to 11,965), Mardin (from 3,701 to 10,426), Sirnak (from 3,081 to 9,368), Hakkari (from 2,232 to 5,166), Siirt (from 2,379 to 5,312).

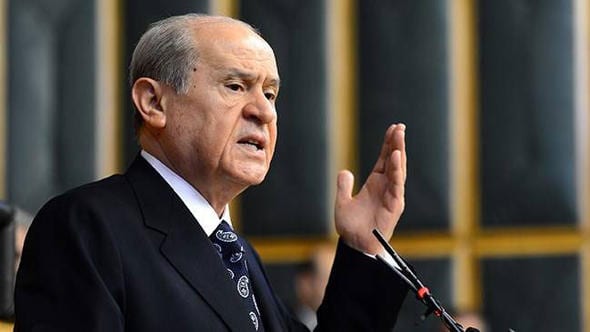

Local observers note the MHP has made no special effort to boost its popularity in the region since the 2015 elections. Bahar Kilicgedik, a long-time journalist in Diyarbakir, told Al-Monitor that the MHP hardly did any campaigning ahead of the June 24 polls. Referring to MHP leader Devlet Bahceli, she said, “Bahceli never came to the region and never held any rallies during the campaign period. I failed to observe any activity on the part of the [MHP’s] provincial branches either. The only things I came across were the Bahceli posters hung on the facades of provincial offices.”

The lack of MHP electioneering, coupled with the party’s sharpened nationalist rhetoric, have led analysts to look to external dynamics to explain the party’s gains in the region.

In an interview with Al-Monitor, researcher and writer Kemal Can pointed to two possible factors: the significant increase in the number of security forces in the region, and the influence of the security bureaucracy.

He said, “The first reason is related to the increase in the number of the security forces, as some local surveys confirm. There is also data suggesting that the voting behavior of the security forces has shifted from the [ruling] Justice and Development Party [AKP] to the MHP. This is not enough to explain fully the numerical increase but could still create small proportional differences.”

The second factor could be the influence of the security bureaucracy and the so-called village guards — government-armed Kurds helping the security forces — “in terms of relocating ballot boxes and controlling and manipulating the voting,” Can said. “They might have used that influence in favor of the MHP. Though hard to prove, this is possible.”

The HDP, too, is struggling to explain the MHP’s gains in the region. The issue will feature in an election report by the party, to be released in the coming days.

In remarks to Al-Monitor, HDP spokesman Ayhan Bilgen drew attention to the so-called 142-code papers, which allow members of the security forces to vote at any ballot box. He suggested that security forces were directed to vote in areas with smaller electorates. “In [relatively bigger] provinces such as Sanliurfa and Mardin, the votes of 3,000 or 5,000 security officers cannot sway the outcome, but in Hakkari, they managed to get one lawmaker elected by directing that many security officers to vote in the region,” he said.

“The second issue is multiple voting,” Bilgen said, stressing that the 142-code papers were prone to abuse, allowing their holders to vote multiple times without detection. “There is no record system to control such voters. We have no idea how many people could have voted multiple times in this way,” he said.

The increase in the number of security forces in the southeast stems from reinforcements sent to the region since 2015, when the authorities launched a massive crackdown on armed Kurdish militants holed up in urban areas. More police and soldiers are said to have been sent to the region ahead of the elections, increasing the number of those who could vote without being registered at a specific ballot box.

When it comes to the HDP, its own showing in the region also defied expectations. Though the party managed to surpass the 10% national threshold to enter parliament, the support it received from local Kurds was well below what it had hoped for in the face of the mounting nationalist rhetoric of both the MHP and the AKP. Most notably, conservative Kurds disgruntled with the AKP had been expected to gravitate to the HDP. The results, however, show the opposite.

For Bilgen, this also has to do with external factors. The loss of votes is observed mostly in areas such as Nusaybin and Kiziltepe, which suffered the most in the 2015-2016 crackdown, he said. “The voter loss in those areas is 20-25%. Those people saw their neighborhoods destroyed and lost their homes. There was significant migration. We will analyze electoral registers to make a definitive conclusion,” Bilgen added.

On a self-critical note, Bilgen said the party underperformed in bringing its voters to the ballot boxes, noting that many Kurds had moved to western provinces as seasonal workers during the summer. “Similarly, our organization was not strong enough in terms of the distribution of ballot box overseers,” he added.

The spokesman stressed that almost all invalidated votes in the region were HDP votes. About 300,000 HDP votes were classed as invalid during the count, he said. This is a significant figure, given that the number of votes that propelled President Recep Tayyip Erdogan over the 50% mark for a first-round victory in the presidential polls was about 700,000.

The heavy influence of external factors leaves little room for a political analysis of the results. Neither the HDP nor the MHP appears likely to make any fundamental changes to its Kurdish policies based on the results.

“I don’t expect the MHP to consider softening its Kurdish policy in light of the vote it got from the region,” Can said, adding, “On the contrary, if the vote increase is really due to the reasons we contemplate [the influence of the security bureaucracy], this was achieved exactly because the MHP opted for a hard-line rhetoric.”

Stressing that voter shifts from the AKP to the MHP were observed across Turkey, Can said, “The AKP’s increase of the nationalist dosage served the MHP.”

Bilgen, for his part, conceded that Kurds could have seen shortcomings or weaknesses in the HDP. “Yet this does not mean that there is a better alternative than the HDP, but that they see shortcomings,” he said. “Voters have [expressed] objections and criticism of the HDP, and we will analyze those as well.”